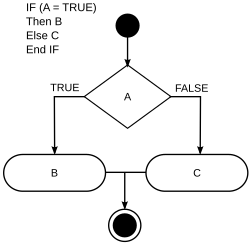

Conditional (computer programming)  In computer science, conditionals (that is, conditional statements, conditional expressions and conditional constructs) are programming language constructs that perform different computations or actions or return different values depending on the value of a Boolean expression, called a condition. Conditionals are typically implemented by selectively executing instructions. Although dynamic dispatch is not usually classified as a conditional construct, it is another way to select between alternatives at runtime. TerminologyConditional statements are imperative constructs executed for side-effect, while conditional expressions return values. Many programming languages (such as C) have distinct conditional statements and conditional expressions. Although in pure functional programming, conditional expressions do not have side-effects, many languages with conditional expressions (such as Lisp) support conditional side-effects. If–then(–else)The If (Boolean condition) Then

(consequent)

Else

(alternative)

End If

For example: If stock = 0 Then

message = order new stock

Else

message = there is stock

End If

In the example code above, the part represented by (Boolean condition) constitutes a conditional expression, having intrinsic value (e.g., it may be substituted by either of the values When an interpreter finds an After either branch has been executed, control returns to the point after the History and developmentIn early programming languages, especially some dialects of BASIC in the 1980s home computers, an The "dangling else" problemThe if a then if b then s else s2 can be parsed as if a then (if b then s) else s2 or if a then (if b then s else s2) depending on whether the Else ifBy using if condition then

-- statements

elseif condition then

-- more statements

elseif condition then

-- more statements;

...

else

-- other statements;

end if;

For example, for a shop offering as much as a 30% discount for an item: if discount < 11% then

print (you have to pay $30)

elseif discount < 21% then

print (you have to pay $20)

elseif discount < 31% then

print (you have to pay $10)

end if;

In the example above, if the discount is 10%, then the first if statement will be evaluated as true and "you have to pay $30" will be printed out. All other statements below that first if statement will be skipped. The However, in many languages more directly descended from Algol, such as Simula, Pascal, BCPL and C, this special syntax for the This design choice has a slight "cost". Each If all terms in the sequence of conditionals are testing the value of a single expression (e.g., If–then–else expressionsMany languages support conditional expressions, which are similar to if statements, but return a value as a result. Thus, they are true expressions (which evaluate to a value), not statements (which may not be permitted in the context of a value). The concept of conditional expressions was first developed by John McCarthy during his research into symbolic processing and LISP in the late 1950s. Algol familyALGOL 60 and some other members of the ALGOL family allow myvariable := if x > 20 then 1 else 2 Lisp dialectsConditional expressions have always been a fundamental part of Lisp . In pure LISP, the ;; Scheme

(define (myvariable x) (if (> x 12) 1 2)) ; Assigns 'myvariable' to 1 or 2, depending on the value of 'x'

;; Common Lisp

(let ((x 10))

(setq myvariable (if (> x 12) 2 4))) ; Assigns 'myvariable' to 2

HaskellIn Haskell 98, there is only an if expression, no if statement, and the Because Haskell is lazy, it is possible to write control structures, such as if, as ordinary expressions; the lazy evaluation means that an if function can evaluate only the condition and proper branch (where a strict language would evaluate all three). It can be written like this:[5] if' :: Bool -> a -> a -> a

if' True x _ = x

if' False _ y = y

C-like languagesC and C-like languages have a special ternary operator (?:) for conditional expressions with a function that may be described by a template like this: This means that it can be inlined into expressions, unlike if-statements, in C-like languages: my_variable = x > 10 ? "foo" : "bar"; // In C-like languages

which can be compared to the Algol-family if–then–else expressions (in contrast to a statement) (and similar in Ruby and Scala, among others). To accomplish the same using an if-statement, this would take more than one line of code (under typical layout conventions), and require mentioning "my_variable" twice: if (x > 10)

my_variable = "foo";

else

my_variable = "bar";

Some argue that the explicit if/then statement is easier to read and that it may compile to more efficient code than the ternary operator,[6] while others argue that concise expressions are easier to read than statements spread over several lines containing repetition. Visual BasicIn Visual Basic and some other languages, a function called TclIn Tcl if {$x > 10} {

puts "Foo!"

}

invokes a function named In the above example the condition is not evaluated before calling the function. Instead, the implementation of the Such a behavior is possible by using

Because

RustIn Rust, // Assign my_variable some value, depending on the value of x

let my_variable = if x > 20 {

1

} else {

2

};

// This variant will not compile because 1 and () have different types

let my_variable = if x > 20 {

1

};

// Values can be omitted when not needed

if x > 20 {

println!("x is greater than 20");

}

Guarded conditionalsThe Guarded Command Language (GCL) of Edsger Dijkstra supports conditional execution as a list of commands consisting of a Boolean-valued guard (corresponding to a condition) and its corresponding statement. In GCL, exactly one of the statements whose guards is true is evaluated, but which one is arbitrary. In this code if G0 → S0 □ G1 → S1 ... □ Gn → Sn fi the Gi's are the guards and the Si's are the statements. If none of the guards is true, the program's behavior is undefined. GCL is intended primarily for reasoning about programs, but similar notations have been implemented in Concurrent Pascal and occam. Arithmetic ifUp to Fortran 77, the language Fortran has had an arithmetic if statement which jumps to one of three labels depending on whether its argument e is e < 0, e = 0, e > 0. This was the earliest conditional statement in Fortran.[11] SyntaxIF (e) label1, label2, label3

Where e is a numeric expression of type SemanticsThis is equivalent to this sequence, where e is evaluated only once. IF (e .LT. 0) GOTO label1

IF (e .EQ. 0) GOTO label2

IF (e .GT. 0) GOTO label3

StylisticsArithmetic if is an unstructured control statement, and is not used in structured programming. In practice it has been observed that most arithmetic This was the only conditional control statement in the original implementation of Fortran on the IBM 704 computer. On that computer the test-and-branch op-code had three addresses for those three states. Other computers would have "flag" registers such as positive, zero, negative, even, overflow, carry, associated with the last arithmetic operations and would use instructions such as 'Branch if accumulator negative' then 'Branch if accumulator zero' or similar. Note that the expression is evaluated once only, and in cases such as integer arithmetic where overflow may occur, the overflow or carry flags would be considered also. Object-oriented implementation in SmalltalkIn contrast to other languages, in Smalltalk the conditional statement is not a language construct but defined in the class var = condition

ifTrue: [ 'foo' ]

ifFalse: [ 'bar' ]

JavaScriptJavaScript uses if-else statements similar to those in C languages. A Boolean value is accepted within parentheses between the reserved if keyword and a left curly bracket. if (Math.random() < 0.5) {

console.log("You got Heads!");

} else {

console.log("You got Tails!");

}

The above example takes the conditional of var x = Math.random();

if (x < 1/3) {

console.log("One person won!");

} else if (x < 2/3) {

console.log("Two people won!");

} else {

console.log("It's a three-way tie!");

}

Lambda calculusIn Lambda calculus, the concept of an if-then-else conditional can be expressed using the following expressions: true = λx. λy. x false = λx. λy. y ifThenElse = (λc. λx. λy. (c x y))

note: if ifThenElse is passed two functions as the left and right conditionals; it is necessary to also pass an empty tuple () to the result of ifThenElse in order to actually call the chosen function, otherwise ifThenElse will just return the function object without getting called. In a system where numbers can be used without definition (like Lisp, Traditional paper math, so on), the above can be expressed as a single closure below: ((λtrue. λfalse. λifThenElse.

(ifThenElse true 2 3)

)(λx. λy. x)(λx. λy. y)(λc. λl. λr. c l r))

Here, true, false, and ifThenElse are bound to their respective definitions which are passed to their scope at the end of their block. A working JavaScript analogy(using only functions of single variable for rigor) to this is as follows: var computationResult = ((_true => _false => _ifThenElse =>

_ifThenElse(_true)(2)(3)

)(x => y => x)(x => y => y)(c => x => y => c(x)(y)));

The code above with multivariable functions looks like this: var computationResult = ((_true, _false, _ifThenElse) =>

_ifThenElse(_true, 2, 3)

)((x, y) => x, (x, y) => y, (c, x, y) => c(x, y));

Another version of the earlier example without a system where numbers are assumed is below. The first example shows the first branch being taken, while second example shows the second branch being taken. ((λtrue. λfalse. λifThenElse.

(ifThenElse true (λFirstBranch. FirstBranch) (λSecondBranch. SecondBranch))

)(λx. λy. x)(λx. λy. y)(λc. λl. λr. c l r))

((λtrue. λfalse. λifThenElse.

(ifThenElse false (λFirstBranch. FirstBranch) (λSecondBranch. SecondBranch))

)(λx. λy. x)(λx. λy. y)(λc. λl. λr. c l r))

Smalltalk uses a similar idea for its true and false representations, with True and False being singleton objects that respond to messages ifTrue/ifFalse differently. Haskell used to use this exact model for its Boolean type, but at the time of writing, most Haskell programs use syntactic sugar "if a then b else c" construct which unlike ifThenElse does not compose unless either wrapped in another function or re-implemented as shown in The Haskell section of this page. Case and switch statementsSwitch statements (in some languages, case statements or multiway branches) compare a given value with specified constants and take action according to the first constant to match. There is usually a provision for a default action ('else','otherwise') to be taken if no match succeeds. Switch statements can allow compiler optimizations, such as lookup tables. In dynamic languages, the cases may not be limited to constant expressions, and might extend to pattern matching, as in the shell script example on the right, where the '*)' implements the default case as a regular expression matching any string.

Pattern matchingPattern matching may be seen as an alternative to both if–then–else, and case statements. It is available in many programming languages with functional programming features, such as Wolfram Language, ML and many others. Here is a simple example written in the OCaml language: match fruit with

| "apple" -> cook pie

| "coconut" -> cook dango_mochi

| "banana" -> mix;;

The power of pattern matching is the ability to concisely match not only actions but also values to patterns of data. Here is an example written in Haskell which illustrates both of these features: map _ [] = []

map f (h : t) = f h : map f t

This code defines a function map, which applies the first argument (a function) to each of the elements of the second argument (a list), and returns the resulting list. The two lines are the two definitions of the function for the two kinds of arguments possible in this case – one where the list is empty (just return an empty list) and the other case where the list is not empty. Pattern matching is not strictly speaking always a choice construct, because it is possible in Haskell to write only one alternative, which is guaranteed to always be matched – in this situation, it is not being used as a choice construct, but simply as a way to bind names to values. However, it is frequently used as a choice construct in the languages in which it is available. Hash-based conditionalsIn programming languages that have associative arrays or comparable data structures, such as Python, Perl, PHP or Objective-C, it is idiomatic to use them to implement conditional assignment.[13] pet = input("Enter the type of pet you want to name: ")

known_pets = {

"Dog": "Fido",

"Cat": "Meowsles",

"Bird": "Tweety",

}

my_name = known_pets[pet]

In languages that have anonymous functions or that allow a programmer to assign a named function to a variable reference, conditional flow can be implemented by using a hash as a dispatch table. PredicationAn alternative to conditional branch instructions is predication. Predication is an architectural feature that enables instructions to be conditionally executed instead of modifying the control flow. Choice system cross referenceThis table refers to the most recent language specification of each language. For languages that do not have a specification, the latest officially released implementation is referred to.

See also

References

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia