жӯҙеҸІзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰ

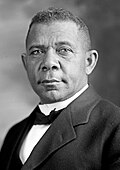

жӯҙеҸІзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰ[1]пјҲгӮҢгҒҚгҒ—гҒҰгҒҚгҒ“гҒҸгҒҳгӮ“гҒ гҒ„гҒҢгҒҸгҖҒиӢұиӘһ: Historically black colleges and universitiesгҖҒHBCUпјүгҒҜгҖҒгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәеӯҰз”ҹгҒ®ж•ҷиӮІгӮ’зӣ®зҡ„гҒЁгҒ—гҒҰ1964е№ҙе…¬ж°‘жЁ©жі•д»ҘеүҚгҒ«иЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«еҗҲиЎҶеӣҪгҒ®й«ҳзӯүж•ҷиӮІж©ҹй–ўгҒ§гҒӮгӮӢ[2]гҖӮгҒқгҒ®еӨҡгҒҸгҒҜеҚ—йғЁгҒ«гҒӮгӮҠгҖҒеҚ—еҢ—жҲҰдәүеҫҢгҒ®гғӘгӮігғігӮ№гғҲгғ©гӮҜгӮ·гғ§гғіжңҹ(1865вҖ“1877)гҒ®й–“гҒ«иЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹ[3]гҖӮгҒқгҒ®еҪ“еҲқгҒ®зӣ®зҡ„гҒҜгҖҒзұіеӣҪгҒ®гҒ»гҒЁгӮ“гҒ©гҒ®еӨ§еӯҰгҒҢй»’дәәеӯҰз”ҹгҒ®е…ҘеӯҰгӮ’иӘҚгӮҒгҒӘгҒӢгҒЈгҒҹжҷӮд»ЈгҒ«гҖҒгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ«ж•ҷиӮІгӮ’жҸҗдҫӣгҒҷгӮӢгҒ“гҒЁгҒ§гҒӮгҒЈгҒҹ[4][5]гҖӮ гғӘгӮігғігӮ№гғҲгғ©гӮҜгӮ·гғ§гғіжңҹгҒ«гҒҜгҖҒжӯҙеҸІзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰгҒ®гҒ»гҒЁгӮ“гҒ©гҒҜгғ—гғӯгғҶгӮ№гӮҝгғігғҲгҒ®е®—ж•ҷеӣЈдҪ“гҒ«гӮҲгҒЈгҒҰиЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҖӮеӨҡгҒҸгҒ®е ҙеҗҲгҖҒеҢ—йғЁгҒ«жӢ зӮ№гӮ’зҪ®гҒҸе®—ж•ҷе®Јж•ҷеё«зө„з№”гҒ®ж”ҜжҸҙгӮ’еҸ—гҒ‘гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҖӮ1890е№ҙгҒ«зұіеӣҪиӯ°дјҡгҒҢ第дәҢж¬ЎгғўгғӘгғ«жі•гӮ’еҸҜжұәгҒ—гҒҹгҒ“гҒЁгҒ§зҠ¶жіҒгҒҢеӨүеҢ–гҒ—гҒҹгҖӮгҒ“гҒ®жі•еҫӢгҒ«гҒҠгҒ„гҒҰгҖҒдәәзЁ®йҡ”йӣўж”ҝзӯ–гӮ’гҒЁгҒЈгҒҰгҒ„гӮӢеҚ—йғЁгҒ®и«ёе·һгҒҢеҗҢжі•гҒ®жҒ©жҒөгӮ’еҸ—гҒ‘гӮӢгҒҹгӮҒгҒ«гҒҜгҖҒгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ«е…¬з«ӢгҒ®й«ҳзӯүж•ҷиӮІж©ҹй–ўгӮ’жҸҗдҫӣгҒҷгӮӢгҒ“гҒЁгҒҢзҫ©еӢҷд»ҳгҒ‘гӮүгӮҢгҒҹгҖӮ19дё–зҙҖгҒ«гҒҜгҖҒй»’дәәгӮ„гӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ®еҸ—гҒ‘е…ҘгӮҢгӮ’жӢЎеӨ§гҒҷгӮӢгҒӢгҖҒе°‘ж•°ж°‘ж—Ҹеҗ‘гҒ‘ж•ҷиӮІж©ҹй–ўгҒЁгҒ—гҒҰгҒ®ең°дҪҚгӮ’зҚІеҫ—гҒ—гҒҹж•ҷиӮІж©ҹй–ўгҒҢгҖҒдё»гҒЁгҒ—гҒҰй»’дәәгҒ®еӨ§еӯҰпјҲPBI : Predominantly Black InstitutionsпјүгҒЁгҒӘгҒЈгҒҹ[6]гҖӮ 1865е№ҙгҒ«гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«гҒ®еҘҙйҡ·еҲ¶еәҰгҒҢе»ғжӯўгҒ•гӮҢгҒҰгҒӢгӮүгӮӮ1дё–зҙҖгҒ«гӮҸгҒҹгӮҠгҖҒгӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«еҚ—йғЁи«ёе·һгҒ®гҒ»гҒје…ЁгҒҰгҒ®еӨ§еӯҰгҒҜгҖҒеҚ—йғЁи«ёе·һгҒ®е·һжі•гҒ§гҒӮгӮӢгӮёгғ гғ»гӮҜгғӯгӮҰжі•гҒ®иҰҸе®ҡгҒ«гӮҲгӮҠгҖҒгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ®е…ҘеӯҰгӮ’е…Ёйқўзҡ„гҒ«зҰҒжӯўгҒ—з¶ҡгҒ‘гҒҰгҒҠгӮҠгҖҒгҒҫгҒҹзұіеӣҪеҶ…гҒ®гҒқгҒ®д»–гҒ®ең°еҹҹгҒ®ж•ҷиӮІж©ҹй–ўгӮӮе®ҡе“Ўжһ гӮ’иЁӯгҒ‘гҒҰй»’дәәгҒ®е…ҘеӯҰж•°гӮ’еҲ¶йҷҗгҒ—з¶ҡгҒ‘гҒҰгҒ„гҒҹ[7][8][9][10]гҖӮдјқзөұзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰгҒҜгҖҒгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ«гӮҲгӮҠеӨҡгҒҸгҒ®ж©ҹдјҡгӮ’жҸҗдҫӣгҒҷгӮӢгҒҹгӮҒгҒ«иЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҖҒгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ®дёӯжөҒйҡҺзҙҡгҒ®зўәз«ӢгҒЁжӢЎеӨ§гҒ«еӨ§гҒҚгҒҸиІўзҢ®гҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢ[11][12]гҖӮ1950пҪһ1960е№ҙд»ЈгҒ«гҒҜгҖҒж•ҷиӮІгҒ«гҒҠгҒ‘гӮӢдәәзЁ®е·®еҲҘгӮ’жі•зҡ„гҒ«еј·еҲ¶гҒҷгӮӢгҒ“гҒЁгҒҜзұіеӣҪеҚ—йғЁгӮ’еҗ«гӮҒгҒҹзұіеӣҪе…ЁеҹҹгҒ§дёҖиҲ¬гҒ«зҰҒжӯўгҒ•гӮҢгҖҒгҒқгҒ®д»–гҒ®е·®еҲҘзҰҒжӯўж”ҝзӯ–гӮӮжҺЎз”ЁгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҖӮгҒӢгҒӨгҒҰгҒҜж®ҶгҒ©гҒ®еӯҰз”ҹгҒҢй»’дәәгҒ§гҒӮгҒЈгҒҹгҒҢгҖҒзҸҫеңЁгҒҜеӯҰз”ҹгҒ®еӨҡж§ҳеҢ–гҒҢйҖІгҒҝгҖҒзҷҪдәәгҒ®еӯҰз”ҹгӮӮеӨҡгҒ„гҖӮ зұіеӣҪгҒ«гҒҜ101ж ЎгҒ®дјқзөұзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰгҒҢгҒӮгӮҠпјҲ1930е№ҙд»ЈгҒ«гҒҜ121ж ЎгҒҢеӯҳеңЁгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гҒҹпјүгҖҒзұіеӣҪеҶ…гҒ®е…¬з«ӢгҒЁз§Ғз«ӢгӮ’еҗҲгӮҸгҒӣгҒҹеӨ§еӯҰж•°гҒ®3пј…[13]гӮ’еҚ гӮҒгҒҰгҒ„гӮӢ[14]гҖӮ27ж ЎгҒҢеҚҡеЈ«иӘІзЁӢгҖҒ52ж ЎгҒҢдҝ®еЈ«иӘІзЁӢгҖҒ83ж ЎгҒҢеӯҰеЈ«иӘІзЁӢгҖҒ38ж ЎгҒҢжә–еӯҰеЈ«иӘІзЁӢгӮ’жҸҗдҫӣгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢ[15][16][17]гҖӮ гӮёгғ§гғјгӮёгӮўе·һгҒ®гӮ№гғҡгғ«гғһгғіеӨ§еӯҰгӮ„гҖҒгғҜгӮ·гғігғҲгғіD.C.гҒ®гғҸгғҜгғјгғүеӨ§еӯҰгҖҢй»’дәәгҒ®гғҸгғјгғҗгғјгғүгҖҚгҒӘгҒ©гҒҜзҶұеҝғгҒ«з•ҷеӯҰз”ҹгӮ’иӘҳиҮҙгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢ[18]гҖӮ жӯҙеҸІзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰгҒҜзҸҫеңЁгҖҒгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ®еӨ§еӯҰеҚ’жҘӯз”ҹгҒ®зҙ„20пј…гҖҒгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ®STEMзі»еҚ’жҘӯз”ҹгҒ®25пј…гӮ’иј©еҮәгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢ[19]гҖӮжӯҙеҸІзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰгҒ®еҚ’жҘӯз”ҹгҒ«гҒҜгҖҒе…¬ж°‘жЁ©йҒӢеӢ•жҢҮе°ҺиҖ…гҒ®гғһгғјгғҶгӮЈгғігғ»гғ«гғјгӮөгғјгғ»гӮӯгғігӮ°гғ»гӮёгғҘгғӢгӮўгҖҒзұіеӣҪжңҖй«ҳиЈҒеҲӨжүҖеҲӨдәӢгҒ®гӮөгғјгӮ°гғғгғүгғ»гғһгғјгӮ·гғЈгғ«гҖҒе…ғзұіеӣҪеүҜеӨ§зөұй ҳгҒ®гӮ«гғһгғ©гғ»гғҸгғӘгӮ№гҒӘгҒ©гҒҢгҒ„гӮӢгҖӮ гӮӘгғҗгғһж”ҝжЁ©гҒҜгҖҒHBCUгҒёгҒ®ж”ҜжҸҙгӮ’1700дёҮгғүгғ«жӢЎеӨ§гҒ•гҒӣгҒҹ[20]гҖӮгҒҫгҒҹгҖҒгғҲгғ©гғігғ—ж”ҝжЁ©гҒҜ2019е№ҙгҒ«и¶…е…ҡжҙҫгҒ®жі•жЎҲгҒ«зҪІеҗҚгҒ—гҖҒHBCUгҒёгҒ®е№ҙй–“2е„„5000дёҮгғүгғ«д»ҘдёҠгҒ®ж”ҜжҸҙгӮ’жұәе®ҡгҒ—гҒҹ[21]гҖӮ жӯҙеҸІ з§Ғз«ӢеӯҰж ЎгӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«еҚ—еҢ—жҲҰдәүд»ҘеүҚгҒ«иЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹHBCUгҒ«гҒҜгҖҒ1837е№ҙгҒ®гғҡгғігӮ·гғ«гғҷгғӢгӮўгғ»гғҒгӮ§гӮӨгғӢгғјеӨ§еӯҰ[22]гҖҒ1851е№ҙгҒ®гӮігғӯгғігғ“гӮўзү№еҲҘеҢәеӨ§еӯҰпјҲеүөз«ӢеҪ“жҷӮгҒҜгҖҢгғһгӮӨгғҠгғјжңүиүІдәәзЁ®еҘіеӯҗеӯҰж ЎгҖҚгҒЁгҒ„гҒҶеҗҚз§°пјүгҖҒ1854е№ҙгҒ®гғӘгғігӮ«гғјгғіеӨ§еӯҰгҒӘгҒ©гҒҢгҒӮгӮӢ[23] гҖӮгӮҰгӮЈгғ«гғҗгғјгғ•гӮ©гғјгӮ№еӨ§еӯҰгӮӮгӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«еҚ—еҢ—жҲҰдәүд»ҘеүҚгҒ«иЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹ[24]гҖӮгҒ“гҒ®еӨ§еӯҰгҒҜгҖҒ1856е№ҙгҒ«гӮӘгғҸгӮӨгӮӘе·һгҒ®гӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гғЎгӮҪгӮёгӮ№гғҲзӣЈзқЈж•ҷдјҡгҒЁгҖҒдё»гҒ«зҷҪдәәгҒ®гғЎгӮҪгӮёгӮ№гғҲзӣЈзқЈж•ҷдјҡгҒЁгҒ®еҚ”еҠӣгҒ«гӮҲгӮҠиЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹ[25]гҖӮ HBCU гҒҜеҲқжңҹгҒ®й ғгҒҜзү©иӯ°гӮ’йҶёгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮгҖҢ1847е№ҙе…ЁзұіжңүиүІдәәзЁ®гҒҠгӮҲгҒігҒқгҒ®еҸӢдәәдјҡиӯ°гҖҚгҒ§гҒҜгҖҒжңүеҗҚгҒӘй»’дәәжј”иӘ¬е®¶гғ•гғ¬гғҮгғӘгғғгӮҜгғ»гғҖгӮ°гғ©гӮ№гҖҒгғҳгғігғӘгғјгғ»гғҸгӮӨгғ©гғігғүгғ»гӮ¬гғјгғҚгғғгғҲгҖҒгӮўгғ¬гӮҜгӮөгғігғҖгғјгғ»гӮҜгғ©гғЎгғ«гҒҢгҒқгҒ®гӮҲгҒҶгҒӘй»’дәәй«ҳзӯүж•ҷиӮІж©ҹй–ўгҒ®иҰҒеҗҰгҒ«гҒӨгҒ„гҒҰиӯ°и«–гҒ—гҒҹгҖӮгҒқгҒ“гҒ§гҖҒгӮҜгғ©гғЎгғ«гҒҜдәәзЁ®е·®еҲҘгӮ’еҸ—гҒ‘гҒӘгҒ„з’°еўғгӮ’жҸҗдҫӣгҒҷгӮӢгҒҹгӮҒгҒ«гҒҜ HBCU гҒҢеҝ…иҰҒгҒ гҒЁдё»ејөгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮдёҖж–№гҖҒгғҖгӮ°гғ©гӮ№гҒЁгӮ¬гғјгғҚгғғгғҲгҒҜй»’дәәгҒҢиҮӘгӮүдәәзЁ®йҡ”йӣўгҒҷгӮӢгҒ®гҒҜй»’дәәгӮігғҹгғҘгғӢгғҶгӮЈгҒ«гҒЁгҒЈгҒҰжҗҚгҒ«гҒӘгӮҠгҒҶгӮӢгҒЁдё»ејөгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮеҗҢдјҡиӯ°гҒ®йҒҺеҚҠж•°гҒҜ HBCU гӮ’ж”ҜжҸҙгҒҷгҒ№гҒҚгҒ§гҒӮгӮӢгҒЁжҠ•зҘЁгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮ[иҰҒеҮәе…ё] гҒ»гҒЁгӮ“гҒ©гҒ®HBCUгҒҜгӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«еҚ—еҢ—жҲҰдәүеҫҢгҒ«еҚ—йғЁгҒ«иЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҒҢгҖҒгҒқгҒ®еӨҡгҒҸгҒҜеҢ—йғЁгҒ«жӢ зӮ№гӮ’зҪ®гҒҸе®Јж•ҷеӣЈдҪ“гҖҒзү№гҒ«гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«е®Јж•ҷеҚ”дјҡгҒ®ж”ҜжҸҙгӮ’еҸ—гҒ‘гҒҰгҒ„гҒҹгҖӮи§Јж”ҫеҘҙйҡ·еұҖгҒҜж–°гҒ—гҒ„еӯҰж ЎгҒ®иіҮйҮ‘иӘҝйҒ”гҒ«еӨ§гҒҚгҒӘеҪ№еүІгӮ’жһңгҒҹгҒ—гҒҹ[26][27]гҖӮ гӮўгғҲгғ©гғігӮҝеӨ§еӯҰпјҲзҸҫеңЁгҒ®гӮҜгғ©гғјгӮҜгғ»гӮўгғҲгғ©гғігӮҝеӨ§еӯҰпјүгҒҜгҖҒ1865е№ҙ9жңҲ19ж—ҘгҒ«гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«еҚ—йғЁгҒ§еҲқгӮҒгҒҰгҒ®HBCUгҒЁгҒ—гҒҰиЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҖӮгӮўгғҲгғ©гғігӮҝеӨ§еӯҰгҒҜгҖҒзұіеӣҪеҶ…гҒ§еҲқгӮҒгҒҰгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ«еӯҰдҪҚгӮ’жҺҲдёҺгҒ—гҒҹеӨ§еӯҰйҷўгҒ§гҒӮгӮҠгҖҒеҚ—йғЁгҒ§еҲқгӮҒгҒҰгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ«еӯҰеЈ«еҸ·гӮ’жҺҲдёҺгҒ—гҒҹеӨ§еӯҰгҒ§гҒӮгӮӢгҖӮгӮҜгғ©гғјгӮҜгғ»гӮ«гғ¬гғғгӮёпјҲ1869е№ҙпјүгҒҜгҖҒгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ®еӯҰз”ҹгӮ’еҜҫиұЎгҒЁгҒҷгӮӢеӣҪеҶ…еҲқгҒ®4е№ҙеҲ¶гғӘгғҷгғ©гғ«гғ»гӮўгғјгғ„гғ»гӮ«гғ¬гғғгӮёгҒ§гҒӮгӮӢгҖӮгҒ“гҒ®2ж ЎгҒҜ1988е№ҙгҒ«зөұеҗҲгҒ•гӮҢгҖҒгӮҜгғ©гғјгӮҜгғ»гӮўгғҲгғ©гғігӮҝеӨ§еӯҰгҒЁгҒӘгҒЈгҒҹ[28]гҖӮгӮ·гғ§гғјеӨ§еӯҰгҒҜ1865е№ҙ12жңҲ1ж—ҘгҒ«иЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҖҒзұіеӣҪеҚ—йғЁгҒ§2з•Әзӣ®гҒ«иЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹHBCUгҒ§гҒӮгҒЈгҒҹгҖӮ1865е№ҙгҒ«гҒҜгҖҒгӮҰгӮ§гӮ№гғҲгғҗгғјгӮёгғӢгӮўе·һгғҸгғјгғ‘гғјгӮәгғ»гғ•гӮ§гғӘгғјгҒ«гӮ№гғҲгғјгғ©гғјгғ»гӮ«гғ¬гғғгӮёпјҲ1865пҪһ1955е№ҙпјүгӮӮиЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹ[3]гҖӮгӮ№гғҲгғјгғ©гғјеӨ§еӯҰгҒ®ж—§гӮӯгғЈгғігғ‘гӮ№гҒЁе»әзү©гҒҜгҖҒгҒқгҒ®еҫҢгғҸгғјгғ‘гғјгӮәгғ»гғ•гӮ§гғӘгғјеӣҪз«ӢжӯҙеҸІе…¬ең’гҒ«зө„гҒҝиҫјгҒҫгӮҢгҒҹ[29]гҖӮ гҒ“гӮҢгӮүгҒ®еӨ§еӯҰгҒ®гҒ„гҒҸгҒӨгҒӢгҒҜгҖҒжңҖзөӮзҡ„гҒ«ж”ҝеәңгҒ®ж”ҜжҸҙгӮ’еҸ—гҒ‘гҒҰе…¬з«ӢеӨ§еӯҰгҒ«гҒӘгҒЈгҒҹ[30]гҖӮ е…¬з«ӢеӯҰж Ў1862е№ҙ[31]гҖҒйҖЈйӮҰж”ҝеәңгҒ®гғўгғӘгғ«жі•гҒҜеҗ„е·һгҒ«еңҹең°д»ҳдёҺеӨ§еӯҰгӮ’иҰҸе®ҡгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮгғўгғӘгғ«жі•гҒ«еҹәгҒҘгҒ„гҒҰеҢ—йғЁгҒЁиҘҝйғЁгҒ§иЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹж•ҷиӮІж©ҹй–ўгҒҜй»’дәәгҒ«й–Ӣж”ҫгҒ•гӮҢгҒҰгҒ„гҒҹгҖӮгҒ—гҒӢгҒ—гҖҒ17гҒ®е·һ(гҒ»гҒјгҒҷгҒ№гҒҰгҒҢеҚ—йғЁ)гҒ§гҒҜгҖҒеҚ—еҢ—жҲҰдәүеҫҢгӮӮдәәзЁ®йҡ”йӣўеҲ¶еәҰгӮ’зҫ©еӢҷд»ҳгҒ‘гҖҒеңҹең°д»ҳдёҺеӨ§еӯҰгҒӢгӮүй»’дәәеӯҰз”ҹгӮ’жҺ’йҷӨгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гҒҹгҖӮ1870е№ҙд»ЈгҒ«гҒҜгҖҒгғҹгӮ·гӮ·гғғгғ”е·һгҖҒгғҗгғјгӮёгғӢгӮўе·һгҖҒгӮөгӮҰгӮ№гӮ«гғӯгғ©гӮӨгғҠе·һгҒҢгҒқгӮҢгҒһгӮҢ1ж ЎгҒ®гӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ®еӨ§еӯҰ(гӮўгғ«гӮігғјгғіеӨ§еӯҰгҖҒгғҸгғігғ—гғҲгғіеӯҰйҷўгҖҒгӮҜгғ©гғ•гғӘгғіеӨ§еӯҰ)гӮ’еңҹең°д»ҳдёҺеӨ§еӯҰгҒЁгҒ—гҒҰжҢҮе®ҡгҒ—гҒҹ[32]гҖӮгҒ“гӮҢгӮ’еҸ—гҒ‘гҒҰгҖҒиӯ°дјҡгҒҜ1890е№ҙ第2ж¬ЎгғўгғӘгғ«жі•пјҲ1890е№ҙиҫІжҘӯеӨ§еӯҰжі•гҒЁгҒ—гҒҰгӮӮзҹҘгӮүгӮҢгӮӢпјүгӮ’еҸҜжұәгҒ—гҖҒж—ўеӯҳгҒ®еңҹең°д»ҳдёҺеӨ§еӯҰгҒӢгӮүй»’дәәгҒҢжҺ’йҷӨгҒ•гӮҢгҒҰгҒ„гӮӢе ҙеҗҲгҖҒе·һгҒҜй»’дәәгҒ®гҒҹгӮҒгҒ«еҲҘгҒ®еңҹең°д»ҳдёҺеӨ§еӯҰгӮ’иЁӯз«ӢгҒҷгӮӢгҒ“гҒЁгӮ’зҫ©еӢҷд»ҳгҒ‘гҒҹгҖӮHBCUгҒ®еӨҡгҒҸгҒҜгҖҒ第2гғўгғӘгғ«жі•гӮ’жәҖгҒҹгҒҷгҒҹгӮҒгҒ«е·һгҒ«гӮҲгҒЈгҒҰиЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹ[33] гҖӮгҒ“гӮҢгӮүгҒ®еңҹең°д»ҳдёҺеӨ§еӯҰгҒҜгҖҒз ”з©¶гҖҒз¶ҷз¶ҡж•ҷиӮІгҖҒгӮўгӮҰгғҲгғӘгғјгғҒжҙ»еӢ•гҒ®гҒҹгӮҒгҒ«жҜҺе№ҙйҖЈйӮҰж”ҝеәңгҒӢгӮүгҒ®иіҮйҮ‘жҸҙеҠ©гӮ’еҸ—гҒ‘з¶ҡгҒ‘гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢ[17]гҖӮ дё»гҒЁгҒ—гҒҰй»’дәәгҒ®еӨ§еӯҰгҖҢдё»гҒЁгҒ—гҒҰй»’дәәгҒ®еӨ§еӯҰ(Predominantly black institutions : PBI)гҖҚгҒЁгҒҜгҖҒHBCUгҒ®жі•зҡ„гҒӘе®ҡзҫ©гӮ’жәҖгҒҹгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гҒӘгҒ„гҒҢгҖҒдё»гҒ«гӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ®гҒҹгӮҒгҒ«ж•ҷиӮІгӮ’жҸҗдҫӣгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢеӨ§еӯҰгҒ§гҒӮгӮӢ[34]гҖӮPBIгҒ®дҫӢгӮ’гҒ„гҒҸгҒӨгҒӢжҢҷгҒ’гӮӢгҒЁгҖҒгӮёгғ§гғјгӮёгӮўе·һз«ӢеӨ§еӯҰгҖҒгӮ·гӮ«гӮҙе·һз«ӢеӨ§еӯҰгҖҒгғҲгғӘгғӢгғҶгӮЈгғ»гғҜгӮ·гғігғҲгғіеӨ§еӯҰгҖҒгғ•гӮЈгғ©гғҮгғ«гғ•гӮЈгӮўгғ»гӮігғҹгғҘгғӢгғҶгӮЈгғ»гӮ«гғ¬гғғгӮёгҒӘгҒ©гҒҢгҒӮгӮӢ[6][35]гҖӮ гӮ№гғқгғјгғ„1920е№ҙд»ЈгҒӢгӮү1930е№ҙд»ЈгҒ«гҒӢгҒ‘гҒҰгҖҒжӯҙеҸІзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰгҒҜгӮ№гғқгғјгғ„гҒ«еј·гҒ„й–ўеҝғгӮ’жҠұгҒҸгӮҲгҒҶгҒ«гҒӘгҒЈгҒҹгҖӮе·һз«ӢеӨ§еӯҰгҒ§гҒҜгӮ№гғқгғјгғ„гҒҢжҖҘйҖҹгҒ«жҷ®еҸҠгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гҒҹгҒҢгҖҒй»’дәәгҒ®гӮ№гӮҝгғјйҒёжүӢгҒҢжҺЎз”ЁгҒ•гӮҢгӮӢгҒ“гҒЁгҒҜе°‘гҒӘгҒӢгҒЈгҒҹгҖӮй»’дәәеҗ‘гҒ‘ж–°иҒһгҒҜгӮ№гғқгғјгғ„гҒ«гҒҠгҒ‘гӮӢжҲҗеҠҹгӮ’дәәзЁ®зҡ„йҖІжӯ©гҒ®иЁјгҒ—гҒЁгҒ—гҒҰз§°жҸҡгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮй»’дәәеӯҰж ЎгҒҜгӮігғјгғҒгӮ’йӣҮгҒ„гҖҒгӮ№гӮҝгғјйҒёжүӢгӮ’жҺЎз”ЁгҒ—гҒҰиө·з”ЁгҒ—гҖҒзӢ¬иҮӘгҒ®гғӘгғјгӮ°гӮ’иЁӯз«ӢгҒ—гҒҹ[36][37]гҖӮ е№ҫгҒӨгҒӢгҒ®жӯҙеҸІзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰгҒ«гҒҜзӢ¬зү№гҒ®гҖҢHBCUгӮ№гӮҝгӮӨгғ«гҖҚгҒЁз§°гҒ•гӮҢгӮӢгғһгғјгғҒгғігӮ°гғҗгғігғүгҒ®дјқзөұгҒҢгҒӮгӮӢгҖӮеӨ§еӯҰй–“гҒ®гғ•гғғгғҲгғңгғјгғ«гҒ®и©ҰеҗҲгҒ®гғҸгғјгғ•гӮҝгӮӨгғ гӮ·гғ§гғјгҒӘгҒ©гҒ§гғ‘гғ•гӮ©гғјгғһгғігӮ№гӮ’жҠ«йңІгҒ—гҖҒеӨ§еӯҰгҒ®иӘҮгӮҠгӮ„гӮўгӮӨгғҮгғігғҶгӮЈгғҶгӮЈеҪўжҲҗгҒ«иІўзҢ®гҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҖӮAmerican Honda Motor CompanyзӨҫгҒҢгӮ№гғқгғігӮөгғјгҒЁгҒӘгҒЈгҒҰгҖҒдәәж°—гҒ®гҒӮгӮӢHBCUгғҗгғігғүгӮ’жӢӣеҫ…гҒҷгӮӢгҖҢHonda Battle of the BandsгҖҚгҒЁгҒ„гҒҶеӨ§дјҡгӮӮгҒ»гҒјжҜҺе№ҙй–ӢгҒӢгӮҢгҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҖӮ гғҰгғҖгғӨдәәйҒҝйӣЈж°‘1930е№ҙд»ЈгҖҒгғ’гғҲгғ©гғјгҒ®еҸ°й ӯгҒЁгҖҒгғ’гғҲгғ©гғјгҒҢжЁ©еҠӣгӮ’жҸЎгҒЈгҒҹеҫҢгҒ®жҲҰеүҚгғҠгғҒгӮ№гғүгӮӨгғ„гҒ«гҒҠгҒ‘гӮӢеҸҚгғҰгғҖгғӨжі•гҒ®ж–ҪиЎҢеҫҢгҖҒгғЁгғјгғӯгғғгғ‘гҒӢгӮүйҖғгӮҢгҒҹеӨҡгҒҸгҒ®гғҰгғҖгғӨдәәзҹҘиӯҳдәәгҒҢзұіеӣҪгҒ«з§»дҪҸгҒ—гҖҒжӯҙеҸІзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰгҒ§ж•ҷиҒ·гҒ«е°ұгҒ„гҒҹ[38]гҖӮзү№гҒ«1933е№ҙгҒҜгҖҒгҒҫгҒҷгҒҫгҒҷжҠ‘ең§зҡ„гҒ«гҒӘгӮӢгғҠгғҒгӮ№гҒ®ж”ҝзӯ–гҒӢгӮүйҖғгӮҢгӮҲгҒҶгҒЁгҒ—гҒҹеӨҡгҒҸгҒ®гғҰгғҖгғӨдәәеӯҰиҖ…гҒ«гҒЁгҒЈгҒҰеҺігҒ—гҒ„е№ҙгҒ§гҒӮгӮҠ[39]гҖҒзү№гҒ«еӨ§еӯҰгҒ§гҒ®иҒ·гӮ’еүҘеҘӘгҒҷгӮӢжі•еҫӢгҒҢеҸҜжұәгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹеҫҢгҒҜгҒӘгҒҠгҒ•гӮүеҺігҒ—гҒҸгҒӘгҒЈгҒҹ[39]гҖӮгғүгӮӨгғ„еӣҪеӨ–гҒ«зӣ®гӮ’еҗ‘гҒ‘гҒҹгғҰгғҖгғӨдәәгҒҜгҖҒгӮ№гғҡгӮӨгғіеҶ…жҲҰгӮ„гҖҒгғЁгғјгғӯгғғгғ‘гҒ«гҒҠгҒ‘гӮӢдёҖиҲ¬зҡ„гҒӘеҸҚгғҰгғҖгғӨдё»зҫ©гҒӘгҒ©гҒ®зҒҪйӣЈгҒ®гҒҹгӮҒгҖҒд»–гҒ®гғЁгғјгғӯгғғгғ‘и«ёеӣҪгҒ§иҒ·гӮ’иҰӢгҒӨгҒ‘гӮӢгҒ“гҒЁгҒҢгҒ§гҒҚгҒӘгҒӢгҒЈгҒҹ[40][39] гҖӮзұіеӣҪгҒ§гҒҜгҖҒеҪјгӮүгҒҜеӯҰе•Ҹзҡ„гӮӯгғЈгғӘгӮўгӮ’з¶ҡгҒ‘гӮӢгҒ“гҒЁгӮ’жңӣгӮ“гҒ гҒҢгҖҒгҒ”гҒҸе°‘ж•°гӮ’йҷӨгҒ„гҒҰгҖҒдё–з•ҢжҒҗж…ҢжҷӮд»ЈгҒ®гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«гҒ®гӮЁгғӘгғјгғҲж•ҷиӮІж©ҹй–ўгҒ§гҒҜгҒ»гҒЁгӮ“гҒ©еҸ—гҒ‘е…ҘгӮҢгӮүгӮҢгҒӘгҒӢгҒЈгҒҹгҖӮгҒқгӮҢгӮүгҒ®ж•ҷиӮІж©ҹй–ўгҒ«гӮӮеҸҚгғҰгғҖгғӨдё»зҫ©гҒ®еә•жөҒгҒҢгҒӮгҒЈгҒҹ[38][41]гҖӮ гҒ“гҒҶгҒ—гҒҹзҸҫиұЎгҒ®зөҗжһңгҖҒ1933е№ҙгҒӢгӮү1945е№ҙгҒ«гҒӢгҒ‘гҒҰеӨҡгҒҸгҒ®HBCUгҒ§йӣҮз”ЁгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹж•ҷе“ЎгҒ®3еҲҶгҒ®2д»ҘдёҠгҒҢгҖҒгғҠгғҒгӮ№гғүгӮӨгғ„гҒӢгӮүйҖғгӮҢгӮӢгҒҹгӮҒгҒ«зұіеӣҪгҒ«жёЎгҒЈгҒҹдәәгҖ…гҒ§гҒӮгҒЈгҒҹ[42]гҖӮHBCUгҒҜгҖҒгғҰгғҖгғӨдәәж•ҷжҺҲгҒҜеӨ§еӯҰгҒ®дҝЎз”ЁгӮ’й«ҳгӮҒгӮӢгҒ®гҒ«еҪ№з«ӢгҒӨиІҙйҮҚгҒӘж•ҷе“ЎгҒ§гҒӮгӮӢгҒЁиҖғгҒҲгҒҰгҒ„гҒҹ[43]гҖӮHBCUгҒ«гҒҜгҖҒеӨҡж§ҳжҖ§гҒЁгҖҒдәәзЁ®гҖҒе®—ж•ҷгҖҒеҮәиә«еӣҪгҒ«й–ўдҝӮгҒӘгҒҸж©ҹдјҡгӮ’дёҺгҒҲгӮӢгҒ“гҒЁгҒёгҒ®еӣәгҒ„дҝЎеҝөгҒҢгҒӮгҒЈгҒҹ[44]гҖӮHBCUгҒҜе№ізӯүгҒӘеӯҰзҝ’з©әй–“гҒЁгҒ„гҒҶеҪјгӮүгҒ®жҺІгҒ’гӮӢзҗҶжғігҒ«гӮҲгӮҠгҖҒгғҰгғҖгғӨдәәгҒ«гӮӮй–ҖжҲёгӮ’й–ӢгҒ„гҒҰгҒ„гҒҹгҖӮHBCUгҒҜгҖҒеҘіжҖ§гӮ’еҗ«гӮҖгҒҷгҒ№гҒҰгҒ®дәәгҖ…гҒҢеӢүеӯҰгҒҷгӮӢгҒ“гҒЁгӮ’жӯ“иҝҺгҒ•гӮҢгҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҒЁж„ҹгҒҳгӮүгӮҢгӮӢз’°еўғгӮ’дҪңгӮҚгҒҶгҒЁеҠӘгӮҒгҒҰгҒ„гҒҹ[44]гҖӮ 第дәҢж¬Ўдё–з•ҢеӨ§жҲҰHBCU гҒҜзұіеӣҪгҒ®жҲҰдәүйҒӮиЎҢгҒ«еӨҡеӨ§гҒӘиІўзҢ®гӮ’жһңгҒҹгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮгҒқгҒ®дёҖдҫӢгҒҜгӮўгғ©гғҗгғһе·һгҒ® гӮҝгӮ№гӮӯгӮ®гғјеӨ§еӯҰ гҒ§гҖҒгӮҝгӮ№гӮӯгғјгӮ®гғ»гӮЁгӮўгғЎгғі гҒҹгҒЎгҒҜеҗҢеӨ§еӯҰгҒ§и¬ӣзҫ©гҒ«еҸӮеҠ гҒ—гҒӘгҒҢгӮүиЁ“з·ҙгӮ’еҸ—гҒ‘гҒҹ[45][46]гҖӮ гғ•гғӯгғӘгғҖе·һгҒ®й»’дәәзҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰзҫӨ1954 е№ҙгҒ®з”»жңҹзҡ„гҒӘгғ–гғ©гӮҰгғіеҜҫж•ҷиӮІе§”е“ЎдјҡиЈҒеҲӨгҒ®еҲӨжұәгҒ®еҫҢгҖҒгғ•гғӯгғӘгғҖе·һиӯ°дјҡгҒҜгҒ•гҒҫгҒ–гҒҫгҒӘйғЎгҒ®ж”ҜжҸҙгӮ’еҫ—гҒҰгҖҒгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгӮ’еҜҫиұЎгҒ«11ж ЎгҒ®зҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰгӮ’й–ӢиЁӯгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮгҒқгҒ®зӣ®зҡ„гҒҜгҖҒгғ•гғӯгғӘгғҖе·һгҒ§гҒҜеҲҶйӣўгҒҷгӮҢгҒ©гӮӮе№ізӯүгҒӘж•ҷиӮІгҒҢж©ҹиғҪгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҒ“гҒЁгӮ’зӨәгҒҷгҒҹгӮҒгҒ§гҒӮгҒЈгҒҹгҖӮгҒ“гӮҢд»ҘеүҚгҒ«гҒҜгҖҒгғ•гғӯгғӘгғҖе·һгҒ§гӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгӮ’еҜҫиұЎгҒ«гҒ—гҒҹзҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰгҒҜгҖҒ1949 е№ҙгҒ«иЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгғҡгғігӮөгӮігғјгғ©гҒ®гғ–гғғгӮ«гғј T. гғҜгӮ·гғігғҲгғізҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰгҒ®1ж ЎгҒ®гҒҝгҒ§гҒӮгҒЈгҒҹгҖӮж–°гҒҹгҒӘзҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰгҒҜгҖҒгӮ®гғ–гӮ№зҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰ (1957 е№ҙ)гҖҒгғ«гғјгӮәгғҷгғ«гғҲзҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰ (1958 е№ҙ)гҖҒгғңгғ«гӮ·гӮўйғЎзҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰ (1958 е№ҙ)гҖҒгғҸгғігғ—гғҲгғізҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰ (1958 е№ҙ)гҖҒгғӯгғјгӮјгғігӮҰгӮ©гғ«гғүзҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰ (1958 е№ҙ)гҖҒгӮ№гғҜгғӢгғје·қзҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰ (1959 е№ҙ)гҖҒгӮ«гғјгғҗгғјзҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰ (1960 е№ҙ)гҖҒгӮігғӘгӮўгғјгғ»гғ–гғӯгғғгӮ«гғјзҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰ (1960 е№ҙ)гҖҒгғӘгғігӮ«гғјгғізҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰ (1960 е№ҙ)гҖҒгӮёгғЈгӮҜгӮҪгғізҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰ (1961 е№ҙ)гҖҒгӮёгғ§гғігӮҪгғізҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰ (1962 е№ҙ) гҒ§гҒӮгӮӢгҖӮ ж–°гҒ—гҒ„зҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰзҫӨгҒҜй»’дәәй«ҳж ЎгҒ®е»¶й•·гҒЁгҒ—гҒҰе§ӢгҒҫгҒЈгҒҹгҖӮй«ҳж ЎгҒЁеҗҢгҒҳж–ҪиЁӯгӮ’дҪҝгҒ„гҖҒгҒ—гҒ°гҒ—гҒ°ж•ҷе“ЎеӣЈгӮӮеҗҢгҒҳгҒ§гҒӮгҒЈгҒҹгҖӮж•°е№ҙеҫҢгҒ«зӢ¬иҮӘгҒ®ж ЎиҲҺгӮ’е»әгҒҰгҒҹгҒЁгҒ“гӮҚгӮӮгҒӮгҒЈгҒҹгҖӮ1964е№ҙе…¬ж°‘жЁ©жі•гҒҢеҸҜжұәгҒ•гӮҢгҖҒеӯҰж ЎгҒ«гҒҠгҒ‘гӮӢдәәзЁ®йҡ”йӣўгҒҢе»ғжӯўгҒ•гӮҢгӮӢгҒЁгҖҒж–°иЁӯгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹзҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰзҫӨгҒҜгҒҷгҒ№гҒҰзӘҒ然й–үйҺ–гҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҖӮеӯҰз”ҹгҒЁж•ҷе“ЎгҒ®гҒ»гӮ“гҒ®дёҖйғЁгҒ гҒ‘гҒҢгҖҒгҒқгӮҢгҒҫгҒ§зҷҪдәәгҒ гҒ‘гҒ гҒЈгҒҹзҹӯжңҹеӨ§еӯҰгҒ«и»ўж ЎгҒ§гҒҚгҒҹгҒҢгҖҒгҒқгҒ“гҒ§гҒҜгҒӣгҒ„гҒңгҒ„еҶ·ж·ЎгҒӘжӯ“иҝҺгҒ—гҒӢеҸ—гҒ‘гҒӘгҒӢгҒЈгҒҹ[47]гҖӮ 1965д»ҘйҷҚ 1965 е№ҙй«ҳзӯүж•ҷиӮІжі•гҒ®еҶҚжүҝиӘҚгҒ«гӮҲгӮҠгҖҒHBCU гҒ®еӯҰиЎ“зҡ„гҖҒиІЎж”ҝзҡ„гҖҒз®ЎзҗҶзҡ„иғҪеҠӣгӮ’ж”ҜжҸҙгҒҷгӮӢгҒҹгӮҒгҒ«йҖЈйӮҰж”ҝеәңгҒҢ HBCU гҒ«зӣҙжҺҘеҠ©жҲҗйҮ‘гӮ’дәӨд»ҳгҒҷгӮӢгғ—гғӯгӮ°гғ©гғ гҒҢиЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҖӮ[48][49]гҖӮ еҗҢжі•гҒ®гғ‘гғјгғҲ B гҒ§гҒҜгҖҒеҗ„ж•ҷиӮІж©ҹй–ўгҒ®PellеҘЁеӯҰйҮ‘гҒ®еҜҫиұЎгҒЁгҒӘгӮӢе…ҘеӯҰиҖ…ж•°гҖҒеҚ’жҘӯзҺҮгҖҒгҒҠгӮҲгҒігӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒҢйҒҺе°Ҹи©•дҫЎгҒ•гӮҢгҒҰгҒ„гӮӢеҲҶйҮҺгҒ§еӯҰеЈ«еҸ·еҸ–еҫ—еҫҢгҒ®ж•ҷиӮІгӮ’з¶ҷз¶ҡгҒҷгӮӢеҚ’жҘӯз”ҹгҒ®еүІеҗҲгҒ«еҹәгҒҘгҒ„гҒҰиЁҲз®—гҒ•гӮҢгӮӢгҖҒиЁҲз®—ејҸгғҷгғјгӮ№гҒ®еҘЁеӯҰйҮ‘гҒ«гҒӨгҒ„гҒҰе…·дҪ“зҡ„гҒ«иҰҸе®ҡгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҖӮй»’дәәеӯҰз”ҹгҒҢеӨ§йғЁеҲҶгӮ’еҚ гӮҒгӮӢеӨ§еӯҰгҒ§гҒӮгҒЈгҒҰгӮӮгҖҒеҗҲиЎҶеӣҪжңҖй«ҳиЈҒеҲӨжүҖгҒ«гӮҲгӮӢгӮ№гӮҰгӮ§гғғгғҲеҜҫгғҡгӮӨгғігӮҝгғјиЈҒеҲӨ(1950е№ҙ)гҒҠгӮҲгҒігғ–гғ©гӮҰгғіеҜҫж•ҷиӮІе§”е“ЎдјҡиЈҒеҲӨ(1954е№ҙ)гҒ®еҲӨжұә(е…¬з«Ӣж•ҷиӮІж–ҪиЁӯгҒ«гҒҠгҒ‘гӮӢдәәзЁ®е·®еҲҘгӮ’йҒ•жі•гҒЁгҒ—гҒҹиЈҒеҲӨжүҖгҒ®еҲӨжұә)гҒҠгӮҲгҒі1965е№ҙй«ҳзӯүж•ҷиӮІжі•гҒ®ж–ҪиЎҢеҫҢгҒ«иЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹ(гҒҫгҒҹгҒҜгӮўгғ•гғӘгӮ«зі»гӮўгғЎгғӘгӮ«дәәгҒ«й–ҖжҲёгӮ’й–ӢгҒ„гҒҹ)еӨ§еӯҰгҒҜгҖҒHBCUгҒ«еҲҶйЎһгҒ•гӮҢгҒӘгҒ„гҖӮ 1980е№ҙгҖҒгӮёгғҹгғјгғ»гӮ«гғјгӮҝгғјеӨ§зөұй ҳгҒҜгҖҒеӣҪгҒ®е…¬з«ӢгҒҠгӮҲгҒіз§Ғз«ӢгҒ®HBCUгӮ’еј·еҢ–гҒҷгӮӢгҒҹгӮҒгҒ«еҚҒеҲҶгҒӘиіҮжәҗгҒЁиіҮйҮ‘гӮ’й…ҚеҲҶгҒҷгӮӢеӨ§зөұй ҳд»ӨгҒ«зҪІеҗҚгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮеҪјгҒ®еӨ§зөұй ҳд»ӨгҒ«гӮҲгӮҠгҖҒгҖҢжӯҙеҸІзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰгҒ«й–ўгҒҷгӮӢгғӣгғҜгӮӨгғҲгғҸгӮҰгӮ№гҒ®гӮӨгғӢгӮ·гӮўгғҒгғ–гҖҚпјҲWHIHBCUпјүгҒҢеүөиЁӯгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҖӮгҒ“гӮҢгҒҜгҖҒзұіеӣҪж•ҷиӮІзңҒгҒҢйҒӢе–¶гҒҷгӮӢйҖЈйӮҰж”ҝеәңиіҮйҮ‘гҒ«гӮҲгӮӢгғ—гғӯгӮ°гғ©гғ гҒ§гҒӮгӮӢ[50]гҖӮ1989е№ҙгҖҒгӮёгғ§гғјгӮёгғ»Hгғ»Wгғ»гғ–гғғгӮ·гғҘеӨ§зөұй ҳгҒҜгҖҒгӮ«гғјгӮҝгғјеӨ§зөұй ҳгҒ®е…Ҳй§Ҷзҡ„зІҫзҘһгӮ’еј•гҒҚз¶ҷгҒҺгҖҒеӨ§зөұй ҳд»Ө12677еҸ·гҒ«зҪІеҗҚгҒ—гҖҒHBCUгҒ«й–ўгҒҷгӮӢеӨ§зөұй ҳи«®е•Ҹ委員дјҡгӮ’иЁӯз«ӢгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮгҒ“гҒ®е§”е“ЎдјҡгҒҜгҖҒж”ҝеәңгҒЁй•·е®ҳгҒ«гҒ“гӮҢгӮүгҒ®зө„з№”гҒ®е°ҶжқҘгҒ®зҷәеұ•гҒ«гҒӨгҒ„гҒҰеҠ©иЁҖгҒҷгӮӢгӮӮгҒ®гҒ§гҒӮгӮӢ[51]гҖӮ 2001 е№ҙгҒӢгӮүгҖҒгҒ„гҒҸгҒӨгҒӢгҒ® HBCU гҒ®еӣіжӣёйӨЁй•·гҒҹгҒЎгҒҜгҖҒгғӘгӮҪгғјгӮ№гӮ’е…ұжңүгҒ—гҖҒеҚ”еғҚгҒҷгӮӢж–№жі•гҒ«гҒӨгҒ„гҒҰи©ұгҒ—еҗҲгҒ„гӮ’е§ӢгӮҒгҒҹгҖӮ2003 е№ҙгҒ«гҖҒгҒ“гҒ®гғ‘гғјгғҲгғҠгғјгӮ·гғғгғ—гҒҜ HBCUеӣіжӣёйӨЁйҖЈеҗҲ гҒЁгҒ—гҒҰжӯЈејҸгҒ«еҲ¶е®ҡгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҖӮгҒ“гӮҢгҒҜгҖҒгҖҢжӯҙеҸІзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰгҒЁгҒқгҒ®ж§ӢжҲҗе“ЎгӮ’еј·еҢ–гҒҷгӮӢгҒҹгӮҒгҒ«иЁӯиЁҲгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҖҒгҒ•гҒҫгҒ–гҒҫгҒӘгғӘгӮҪгғјгӮ№гӮ’жҸҗдҫӣгҒҷгӮӢгҒ“гҒЁгҒ«е°ӮеҝөгҒҷгӮӢжғ…е ұе°Ӯй–Җ家гҒ®еҚ”еғҚгӮ’ж”ҜжҸҙгҒҷгӮӢгӮігғігӮҪгғјгӮ·гӮўгғ гҖҚгҒ§гҒӮгӮӢ[52]гҖӮ 2015е№ҙгҖҒиӯ°дјҡгҒ§и¶…е…ҡжҙҫгҒ®жӯҙеҸІзҡ„й»’дәәеӨ§еӯҰпјҲHBCUпјүе…ҡе“ЎйӣҶдјҡгҒҢгҖҒзұіеӣҪдёӢйҷўиӯ°е“ЎгҒ®гӮўгғ«гғһгғ»Sгғ»гӮўгғҖгғ гӮ№гҒЁгғ–гғ©гғғгғүгғӘгғјгғ»гғҗгғјгғігҒ«гӮҲгҒЈгҒҰиЁӯз«ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҖӮгҒ“гҒ®е…ҡе“ЎйӣҶдјҡгҒҜгҖҒзұіеӣҪйҖЈйӮҰиӯ°дјҡгҒ§HBCUгҒ®ж“Ғиӯ·гӮ’иЎҢгҒЈгҒҰгҒ„гӮӢ[53] гҖӮ2022е№ҙ5жңҲзҸҫеңЁгҖҒ100дәәгӮ’и¶…гҒҲгӮӢйҒёеҮәж”ҝ治家гҒҢгҒ“гҒ®е…ҡе“ЎйӣҶдјҡгҒ®гғЎгғігғҗгғјгҒ§гҒӮгӮӢ[54]гҖӮ и‘—еҗҚгҒӘеҚ’жҘӯз”ҹ

и„ҡжіЁ

й–ўйҖЈй …зӣ®

еӨ–йғЁгғӘгғігӮҜ |

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia