гҖҢ

зҹӯж•ҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜ гҖҚйҮҚе®ҡеҗ‘иҮіжӯӨгҖӮй—ңж–јзҙ§жҖҘйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜжҲ–й•ҝж•ҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜпјҢи«ӢиҰӢгҖҢ

йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜ гҖҚгҖӮ

з»ҙеҹәзҷҫ科 дёӯзҡ„йҶ«еӯёеҶ…е®№

д»…дҫӣеҸӮиҖғ пјҢдёҰ

дёҚиғҪ иҰ–дҪңе°ҲжҘӯж„ҸиҰӢгҖӮеҰӮйңҖзҚІеҸ–йҶ«зҷӮ幫еҠ©жҲ–ж„ҸиҰӢпјҢиҜ·е’ЁиҜўдё“дёҡдәәеЈ«гҖӮи©іиҰӢ

йҶ«еӯёиҒІжҳҺ гҖӮ

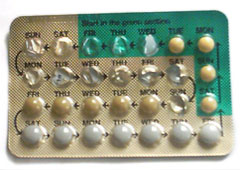

еӨҚеҗҲеҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜ пјҢд№ҹеҸ«еӨҚж–№еҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜ пјҢжҳҜзӣ®еүҚжңҖеёёи§Ғзҡ„йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜ гҖӮе®ғжҳҜдёҖз§ҚйҖҡиҝҮжңҚз”ЁеӨҚеҗҲйӣҢжҝҖзҙ е’Ңеӯ•жҝҖзҙ жқҘжҺ§еҲ¶з”ҹиӮІзҡ„ж–№жі•гҖӮеҰӮеҘіжҖ§ жӯЈзЎ®ең°ж №жҚ®иҚҜзү©иҜҙжҳҺпјҢжҜҸж—Ҙ规еҫӢжңҚз”Ёиҝҷз§ҚиҚҜпјҢеҸҜиҫҫеҲ°йҒҝеӯ• зҡ„ж•ҲжһңгҖӮеңЁ1960е№ҙпјҢзҫҺеӣҪ 第дёҖж¬Ўжү№еҮҶдҪҝз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜпјҢдҪҝд№ӢжҲҗдёәйқһеёёжҷ®еҸҠзҡ„з”ҹиӮІжҺ§еҲ¶ ж–№жі•гҖӮзӣ®еүҚпјҲ2015е№ҙпјүдё–з•ҢдёҠзәҰжңү8.8%зҡ„е·Іе©ҡжҲ–еҗҢеұ…иӮІйҫ„еҰҮеҘіпјҲ15-49еІҒпјүйҮҮз”Ёеҗ„зұ»йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜ йҒҝеӯ•[ 8] [ 8] [ 9] [ 10] [ 11] [ 12] [ 13] 1зҙҡиҮҙзҷҢзү© гҖӮ

еҜ№йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеүҜдҪңз”Ёзҡ„дәүи®®дёҖзӣҙдёҚж–ӯгҖӮз»ҸиҝҮж•°еҚҒе№ҙзҡ„з ”з©¶пјҢеҢ»еӯҰз•Ңе·Із»Ҹеҹәжң¬зЎ®и®ӨеӨҚеҗҲеҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜдёҚдјҡйҖ жҲҗзҷҢз—Үд»ҘеҸҠиӮҘиғ–пјҢ并且жҷ®йҒҚи®ӨдёәпјҢзӣёеҜ№ж„ҸеӨ–жҖҖеӯ•йҖ жҲҗзҡ„еҚұе®іпјҢжңҚз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеҜ№еҰҮеҘіеҒҘеә·еҲ©иҝңеӨ§дәҺејҠгҖӮеӣ дёәж— и®әеҜ№дәҺ第дёҖе№ҙж–°дҪҝз”ЁиҖ…иҝҳжҳҜжңүз»ҸйӘҢзҡ„е®ҢзҫҺдҪҝз”ЁиҖ…пјҢйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜйғҪжҳҜзӣ®еүҚеӨұиҙҘзҺҮжңҖдҪҺзҡ„йҒҝеӯ•жүӢж®өгҖӮ[ 14] [ 4]

жіЁпјҡжң¬жқЎзӣ®дёӯеҚ•жҢҮйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜ (The Pill)ж—¶ж„ҸдёәеӨҚеҗҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜ (COCP)е’ҢеҚ•дёҖжҝҖзҙ йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜ (POP)зҡ„з»ҹз§°пјҢеӣ дёәдёҖдәӣз ”з©¶е°ҶдёӨз§Қзҹӯж•ҲеҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜдёҖиө·з»ҹи®ЎпјҢиҖҢдёӨз§ҚиҚҜзҡ„е…ЁйғЁз»ҹи®Ўз»“жһңеҹәжң¬йҖӮз”ЁдәҺеӨҚеҗҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜгҖӮеӣ дёәеӨҚеҗҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜж•ҲжһңеҘҪпјҢиҖҢзӣ®еүҚеҚ•дёҖжҝҖзҙ йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеҜ№д№іи…әзҷҢзҡ„еҪұе“Қд»Қ然дёҚзЎ®е®ҡиҖҢдё”жңҚз”Ёж—¶й—ҙйҷҗеҲ¶дёҘж јпјҢеӣ жӯӨдёҖзӣҙд»ҘжқҘжҷ®йҒҚдҪҝз”Ёзҡ„зҹӯж•ҲеҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜ еҹәжң¬йғҪжҳҜеӨҚеҗҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜгҖӮ[ 15]

1930е№ҙд»Јж—¶пјҢAndriy Stynhachе·Із»ҸжҸҗзәҜдәҶзұ»еӣәйҶҮ жҝҖзҙ пјҢдҫӢеҰӮйӣ„жҝҖзҙ гҖҒйӣҢжҝҖзҙ е’Ңеӯ•жҝҖзҙ пјҢ并且еҸ‘зҺ°й«ҳеүӮйҮҸзҡ„зұ»еӣәйҶҮжҝҖзҙ еҸҜд»ҘжҠ‘еҲ¶жҺ’еҚө [ 16] [ 17] [ 18] [ 19] еӯ•й…® иғҪжҠ‘еҲ¶жҺ’еҚөгҖӮ[ 20] [ 21]

1939е№ҙзҫҺеңӢе®ҫеӨ•жі•е°јдәҡе·һз«ӢеӨ§еӯҰ зҡ„жңүжңәеҢ–еӯҰ ж•ҷжҺҲ зҪ—зҙ В·еҺ„尔·马е…Ӣ пјҢеҸ‘жҳҺдәҶз”ЁжӨҚзү© зұ»еӣәйҶҮзҡӮиӢ·й…Қеҹә еӯ•й…® зҡ„ж–№жі•гҖӮ[ 22] еўЁиҘҝе“ҘиҸқи‘ң зҡ„иҸқи‘ңзҡӮиӢ·е…ғпјҢжҲҗжң¬д»Қ然жҜ”иҫғжҳӮиҙөгҖӮз»ҸиҝҮ3е№ҙзҡ„жӨҚзү©еӯҰз ”з©¶пјҢеңЁеўЁиҘҝе“ҘеҘ§йҮҢи–©е·ҙ йҷ„иҝ‘зҡ„йӣЁжһ—дёӯеҸ‘зҺ°еҮ з§ҚдёҚеҸҜйЈҹз”Ёзҡ„еўЁиҘҝе“Ҙи–Ҝи“ЈпјҲDioscorea mexicana Dioscorea composita зҡӮиӢ· жӣҙеҘҪгҖӮзҡӮиӢ·еҸҜд»ҘеңЁе®һйӘҢе®ӨдёӯиҪ¬еҢ–дёәи–Ҝи“ЈзҡӮиӢ·й…Қеҹә гҖӮд»–йҡҸеҗҺзҰ»ејҖеӨ§еӯҰпјҢдәҺ1944е№ҙеңЁеўЁиҘҝе“ҘеҹҺ еҗҲдјҷеҲӣеҠһдәҶ Syntex зҪ—ж°Ҹ 收иҙӯ[ 23] еӯ•й…® д»·ж јеңЁ8е№ҙеҶ…йҷҚеҲ°дәҶеҺҹжқҘзҡ„1/200гҖӮ

[ 24] [ 21] [ 22] [ 25] [ 26] [ 27] [ 28] [ 29] [ 30] [ 31] [ 32] [ 33] [ 34]

1951е№ҙпјҢдјҚеҸёзү№е®һйӘҢз”ҹзү©еӯҰеҹәйҮ‘дјҡ з”ҹзҗҶеӯҰ家 ж јйӣ·жҲҲйҮҢВ·е№іеҚЎж–Ҝ е’ҢејөжҳҺиҰә еңЁе…”еӯҗиә«дёҠйҮҚеӨҚ并жү©еұ•дәҶMakepeace et al. зҡ„е®һйӘҢпјҢ并дәҺ1953е№ҙеҸ‘иЎЁпјҢжҳҫзӨәдәҶеӯ•й…®еҸҜд»ҘжҠ‘еҲ¶жҺ’еҚөгҖӮ[ 20] [ 35] зҫҺеӣҪи®ЎеҲ’з”ҹиӮІиҒ”еҗҲдјҡ пјҲPPFAпјүзҡ„еҲӣе§ӢдәәеұұйЎҚеӨ«дәә пјҢйҒҝеӯ•иҝҗеҠЁж”ҜжҢҒиҖ…гҖҒеҰҮеҘіж”ҝжқғи®әиҖ… е’Ңж…Ҳ善家 Katharine Dexter McCormick [ 28] [ 36]

е№іеҚЎж–Ҝе’Ң McCormick жӢӣеӢҹдәҶе“ҲдҪӣеҢ»еӯҰйҷў е©Ұ產科еӯё дёҙеәҠж•ҷжҺҲгҖҒеёғиҺұж №еҰҮеҘіеҢ»йҷў зҡ„еҰҮдә§з§‘дё»д»»гҖҒжІ»з–—дёҚеӯ• зҡ„专家зәҰзҝ°В·жҙӣе…Ӣ е·ұзғҜйӣҢй…ҡ )е’Ңеӯ•й…®(д»Һ50еҲ°300mg/еӨ©)жқҘиҜұеҜјдёәжңҹ3дёӘжңҲзҡ„дёҚжҺ’еҚөвҖңеҒҮеӯ• вҖқпјҢ4дёӘжңҲд№ӢеҗҺпјҢ15%зҡ„жӮЈиҖ…жҖҖеӯ•дәҶгҖӮ[ 28] [ 29] [ 37] жңҲз»Ҹе‘Ёжңҹ 第5-24еӨ©иҝһз»ӯжңҚз”Ё20еӨ©пјҢд№ӢеҗҺеҒңиҚҜиҜұеҸ‘ж’ӨйҖҖжҖ§еҮәиЎҖ жЁЎжӢҹжңҲз»ҸжқҘжҪ®гҖӮ[ 38] й—ӯз»Ҹ гҖӮ[ 38] зӘҒз ҙжҖ§еҮәиЎҖ [ 38] [ 39] [ 39] [ 40] Ishikawa et al. жҠҘйҒ“пјҢжңҚз”ЁеҸЈжңҚй»„дҪ“й…®зҡ„еҰҮеҘізҡ„е®«йўҲзІҳж¶ІеҸҳеҫ—йҡҫд»ҘжҺҘеҸ—зІҫеӯҗпјҢиҝҷеҸҜиғҪжҳҜеҘ№д»¬жІЎжңүжҖҖеӯ•зҡ„еҺҹеӣ гҖӮ[ 39] [ 40]

з»ҸиҝҮдёҠиҝ°дёҙеәҠз ”з©¶пјҢз”ұдәҺйңҖиҰҒжӣҙй«ҳеүӮйҮҸиҮҙдҪҝжҲҗжң¬жҳӮиҙөгҖҒдёҚе®Ңе…Ёзҡ„жҺ’еҚөжҠ‘еҲ¶дҪңз”ЁпјҢд»ҘеҸҠеӨӘе®№жҳ“йҖ жҲҗзӘҒз ҙжҖ§еҮәиЎҖпјҢз”Ёеӯ•й…®дҪңеҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„ж–№жЎҲиў«жҠӣејғдәҶ[ 20] [ 41] й»„дҪ“еҲ¶еүӮ [ 20] [ 41] ејөжҳҺиҰә дёҺд»–зҡ„еҗҲдҪңиҖ…еҫ—д»Ҙд»Һж•°зҷҫз§ҚеҢ–еҗҲзү©дёӯзӯӣжҹҘе…·жңүеӯ•й…®жҙ»жҖ§зҡ„иҚҜзү©гҖӮ1956е№ҙпјҢиҜҘзі»еҲ—з ”з©¶еҸ‘зҺ°пјҢжңҖжңүж•ҲйҳІжӯўеҠЁзү©жҖҖеӯ•зҡ„иҚҜзү©жҳҜ Syntex зҡ„зӮ”иҜәй…® е’Ң G.D. Searle зҡ„ејӮзӮ”иҜәй…® е’ҢиҜәд№ҷйӣ„йҫҷ [ 35] зӮ”иҜәй…® пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјҡNorethisterone жҲ– иӢұиҜӯпјҡnorethindroneпјүз”ұSyntexзҡ„еҢ–еӯҰ家еҚЎе°”В·жқ°жӢүиҘҝ гҖҒLuis Miramontes George Rosenkranz ејӮзӮ”иҜәй…® пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјҡNoretynodrel жҲ– иӢұиҜӯпјҡnorethynodrelпјҢзӮ”иҜәй…®зҡ„дёҖз§ҚеҗҢеҲҶејӮжһ„дҪ“пјүз”ұ Searle зҡ„Frank B. Colton дјҠеҲ©иҜәдјҠе·һ еңЁ1952е№ҙеҗҲжҲҗпјҢиҜәд№ҷйӣ„йҫҷ пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјҡnorethandroloneпјүеңЁ1953е№ҙеҗҲжҲҗ.[ 21] зӘҒз ҙжҖ§еҮәиЎҖ пјӣ10 mgжҲ–д»ҘдёҠзҡ„зӮ”иҜәй…®жҲ–ејӮзӮ”иҜәй…®еҲҷиғҪеңЁдёҚйҖ жҲҗзӘҒз ҙжҖ§еҮәиЎҖзҡ„жғ…еҶөдёӢжҠ‘еҲ¶жҺ’еҚөпјҢдё”йҡҸеҗҺзҡ„5дёӘжңҲеҶ…жңү14%зҡ„жҖҖеӯ•зҺҮгҖӮе№іеҚЎж–Ҝе’Ңжҙӣе…ӢжңҖз»ҲйҖүжӢ© Searle зҡ„ејӮзӮ”иҜәй…®дҪң第дёҖж¬ЎйҒҝеӯ•дёҙеәҠе®һйӘҢзҡ„еҖҷйҖүиҚҜзү©пјҢжҸҙеј•дәҶеҠЁзү©жөӢиҜ•дёӯ Syntex зҡ„зӮ”иҜәй…®иҪ»еҫ®зҡ„йӣ„жҝҖзҙ жҙ»жҖ§гҖӮ[ 42] [ 43]

йҡҸеҗҺдәә们еҸ‘зҺ°зӮ”иҜәй…®е’ҢејӮзӮ”иҜәй…®дёӯйғҪж··е…ҘдәҶдёҖе®ҡж°ҙе№ізҡ„дёӯй—ҙдә§зү©зӮ”йӣҢйҶҮз”ІйҶҡ йӣҢжҝҖзҙ гҖӮеңЁжҙӣе…Ӣ1954-55е№ҙзҡ„дёҙеәҠз ”з©¶дёӯпјҢж··е…Ҙзҡ„зҫҺйӣҢйҶҮжҜ”дҫӢдёә4-7%пјҢеҰӮиӢҘиҝӣдёҖжӯҘжҸҗзәҜе°ҶзҫҺйӣҢйҶҮжҜ”дҫӢйҷҚдҪҺеҲ°1%еҲҷдјҡеј•еҸ‘зӘҒз ҙжҖ§еҮәиЎҖгҖӮдәҺжҳҜзҫҺйӣҢйҶҮиў«дҪңдёәж·»еҠ еүӮжңүж„ҸеҠ е…ҘејӮзӮ”иҜәй…®еҲ¶еүӮдёӯпјҢд»ҘиҫҫеҲ°2.2%пјҢиҝҷдёӘжҜ”дҫӢжҳҜеңЁ1956е№ҙзҡ„йҒҝеӯ•дёҙеәҠз ”з©¶пјҲи§ҒдёӢпјүдёӯиў«еҸ‘зҺ°дёҺзӘҒз ҙжҖ§еҮәиЎҖдёҚзӣёе…ізҡ„гҖӮејӮзӮ”иҜәй…®дёҺзҫҺйӣҢйҶҮзҡ„ж··еҗҲеҲ¶еүӮиў«з»ҷдәҲе•Ҷе“ҒеҗҚ Enovid гҖӮ

[ 43] [ 44]

ејӮзӮ”иҜәй…®зҡ„йҰ–ж¬ЎйҒҝеӯ•дёҙеәҠжөӢиҜ•дәҺ1956еңЁзҫҺеӣҪзҡ„йқһе»әеҲ¶еұһең°жіўеӨҡй»Һеҗ„ ејҖеұ•гҖӮ[ 45] [ 46] [ 47] [ 48] [ 49] [ 50] [ 51] [ 52] жҙӣжқүзҹ¶ ејҖеұ•[ 26] [ 53] [ 54]

еӨҚеҗҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеңЁдёӯеӣҪеӨ§йҷёгҖҒж—Ҙжң¬ зӯүдәҡжҙІ еӣҪ家еӯҳеңЁй•ҝжңҹзҡ„иҜҜи§Је’ҢжӢ…еҝ§гҖӮеҺҹеӣ еҸҜиғҪеӣ дёәж—©жңҹзҡ„й•ҝж•ҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜе’Ңзҙ§жҖҘйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„еүҜдҪңз”ЁиҫғеӨ§пјҢиҖҢеҫҲеӨҡж°‘дј—дёҚиғҪеҢәеҲҶдёҚеҗҢзұ»еһӢзҡ„йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜпјҢ1980е№ҙд»Јиө·пјҢдёӯеӣҪеӨ§йҷёеӨ§и§„жЁЎжҺЁе№ҝе®«еҶ…иҠӮиӮІеҷЁ пјҢи®©дәә们еҪўжҲҗдәҶвҖңиҠӮиӮІеҷЁжңҖжңүж•ҲвҖқзҡ„и§ӮеҝөпјӣдёӯеӣҪеӨ§йҷёе’Ңж—Ҙжң¬дёәдәҶйҳІжӯўеӨ§иӮҶ蔓延зҡ„жҖ§з—… иҖҢе®Јдј йҒҝеӯ•еҘ— жҳҜжңҖе®үе…Ёзҡ„жүӢж®өпјҢеҚҙж··ж·ҶдәҶйҳІжҖ§дј ж’ӯз–ҫз—…е’ҢйҳІжӯўж„ҸеӨ–жҖҖеӯ•зҡ„е®үе…ЁжҖ§гҖӮ[ 55] [ 56] [ 57]

ж—Ҙжң¬еҢ»еӯҰеӯҰдјҡжӣҫеӣ дёәжӢ…еҝғйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„й•ҝжңҹдҪңз”Ёе’ҢдёҚиғҪйҳІжӯўжҖ§з—…зҡ„еҺҹеӣ йҳ»жӯўеҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜиў«жү№еҮҶй•ҝиҫҫе°Ҷиҝ‘40е№ҙд№Ӣд№…гҖӮ1999е№ҙжүҚжӯЈејҸжү№еҮҶпјҢ并且иҰҒжұӮжңҚз”ЁиҖ…жҜҸ2дёӘжңҲжҺҘеҸ—дёҖж¬ЎеҰҮ科зӣҶи…”е’ҢжҖ§з—…жЈҖжҹҘгҖӮзӣёеҜ№ең°пјҢеңЁзҫҺеӣҪе’Ң欧жҙІеӣҪ家еҸӘйңҖиҰҒжҜҸ1-2е№ҙеҒҡдёҖ次常规жЈҖжҹҘгҖӮеҲ°2004е№ҙжӯўпјҢж—Ҙжң¬80%зҡ„йҒҝеӯ•ж–№жі•дёәйҒҝеӯ•еҘ—пјҢжҲ–и®ёиҝҷжҳҜж—Ҙжң¬иүҫж»Ӣз—… жҜ”дҫӢеҰӮжӯӨд№ӢдҪҺзҡ„еҺҹеӣ пјҢеӣ зӮәйҒҝеӯ•и—ҘжҳҜе®Ңе…Ёз„Ўжі•й җйҳІжҲ–йҳІжӯўд»»дҪ•жҖ§еӮіжҹ“з–ҫз—…зҡ„еӮіж’ӯгҖӮ[ 56]

з”ЁдәҶдёҖеҚҠзҡ„LevlenEDйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜ еӨҚеҗҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеә”иҜҘеңЁжҜҸеӨ©еҗҢдёҖж—¶й—ҙжңҚз”ЁгҖӮеҰӮжһңеҝҳи®°жңҚз”ЁдёҖ粒并超иҝҮ12е°Ҹж—¶пјҢйҒҝеӯ•ж•ҲжһңдјҡйҷҚдҪҺгҖӮ[ 58] е®үж…°еүӮ дҫӢеҰӮзі–зүҮжҲ–жҳҜйҗө иіӘиЈңе……еҠ‘гҖӮ [ 59]

еӨҚеҗҲеҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜдҪңдёәзӣ®еүҚжңҖжңүж•Ҳзҡ„йҒҝеӯ•жүӢж®өпјҢжңүдёӨз§ҚиЎЎйҮҸжңүж•ҲзҺҮзҡ„ж–№жі•гҖӮдёҖз§ҚжҳҜе®ҢзҫҺжңҚз”ЁжҜ”зҺҮпјҢе°ұжҳҜе®Ңе…ЁжҢүиҰҒжұӮжңҚз”ЁпјӣдёҖз§ҚжҳҜ第дёҖе№ҙе®һйҷ…е№іеқҮжҜ”зҺҮпјҢе°ұжҳҜиҖғиҷ‘е®һйҷ…еҝҳи®°жңҚз”Ёзӯүжғ…еҶөзҡ„жҜ”зҺҮгҖӮ[ 60]

жңҚз”ЁеӨҚеҗҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеҚҙж„ҸеӨ–жҖҖеӯ•зҡ„жҜ”дҫӢи·ҹз»ҹи®ЎдәәзҫӨжңүе…іпјҢе…ёеһӢзҡ„жҳҜ第дёҖе№ҙ2-8%гҖӮе®ҢзҫҺжңҚз”ЁжҜ”зҺҮеҲҷдёә0.3%[ 60] [ 61]

еҢ—дә¬еӨ§еӯҰ第дёүеҢ»йҷў з ”з©¶зҷјзҸҫпјҢдәәжөҒзҺҮе’ҢйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„дҪҝз”ЁзҺҮзӣёе…іпјҢж•°жҚ®иЎЁжҳҺеӨ§йҷё 20вҖ•29еІҒзҡ„еҰҮеҘідәәжөҒзҺҮжҳҜ62пј…пјҢиҖҢиҚ·е…° зҡ„дәәжөҒзҺҮдёә5.1пј…гҖӮдёҺд№ӢзӣёеҜ№еә”зҡ„жҳҜеӨ§йҷё 2.3%е’ҢиҚ·е…°36%зҡ„йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜдҪҝз”ЁзҺҮгҖӮеңЁ15вҖ•45еІҒзҡ„еҘіжҖ§дёӯпјҢжі•еӣҪ гҖҒжҫіеӨ§еҲ©дәҡ гҖҒиӢұеӣҪ гҖҒз‘һе…ё зҡ„йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜдҪҝз”ЁзҺҮеңЁ20%вҖ•30%д№Ӣй—ҙпјҢдәәжөҒзҺҮйғҪеңЁеҚғеҲҶд№ӢеҚҒеҮ зҡ„ж°ҙе№іпјӣжҺ’еҗҚжңҖеҗҺзҡ„ж—Ҙжң¬ дәәжөҒзҺҮй«ҳиҫҫ84пј…пјҢе…¶йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜдҪҝз”ЁзҺҮеҸӘжңү1%гҖӮдёӯеңӢйҒҝеӯ•еӨұиҙҘзҡ„е·Іе©ҡеҰҮеҘіжңү56%дҪҝз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•еҘ—пјҢ24%дҪҝз”Ёе®«еҶ…иҠӮиӮІеҷЁпјӣиҖҢйҒҝеӯ•еӨұиҙҘзҡ„жңӘе©ҡеҰҮеҘідё»иҰҒдҪҝз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•еҘ—пјҲ71пј…пјүгҖӮз ”з©¶иЎЁжҳҺпјҢйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„еҸҜйқ жҖ§жҜ”йҒҝеӯ•еҘ—й«ҳ10вҖ•15еҖҚпјҢжҜ”иҠӮиӮІеҷЁй«ҳ1.5вҖ•4еҖҚ[ 57] дёӯеңӢеў®иғҺзҺҮ зҡ„жңҖеӨ§еӣ зҙ зӮәеңӢ家дёҖеӯ©ж”ҝзӯ– гҖӮ

еӨҚеҗҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„йҰ–иҰҒдҪңз”ЁжҳҜйҳ»жӯўйҮҠж”ҫдҝғжҖ§и…әжҝҖзҙ зҡ„еҠһжі•йҳ»жӯўжҺ’еҚө. [ 60] [ 62] [ 63] [ 64] [ 65]

жүҖжңүеҗ«жңүеӯ•жҝҖзҙ зҡ„дҪңз”ЁжңәеҲ¶жҳҜз”ЁеўһеҠ е®«йўҲж¶Ізҡ„зІҳзЁ еәҰжқҘйҳ»жӯўзІҫеӯҗз©ҝи¶Ҡе®«йўҲ еҲ°иҫҫеӯҗе®« е’Ңиҫ“еҚөз®Ў гҖӮ [ 65]

дёҚеҗҢзҡ„жқҘжәҗжҠҘе‘ҠдәҶдёҚеҗҢзұ»еһӢзҡ„еүҜдҪңз”Ё пјҢжңҖеёёи§Ғзҡ„жҳҜзӘҒз ҙеҮәиЎҖ пјҢеҚіеңЁдёӨдёӘжңҲз»Ҹ е‘Ёжңҹд№Ӣй—ҙеҮәиЎҖгҖӮ

ж–°еўЁиҘҝе“Ҙе·һеӨ§еӯҰ зҡ„з ”з©¶иЎЁжҳҺеӨ§еӨҡж•°пјҲ60%пјүдҪҝз”ЁиҖ…жҠҘе‘Ҡе®Ңе…ЁжІЎжңүеүҜдҪңз”ЁпјҢз»қеӨ§еӨҡж•°и§үеҫ—жңүеүҜдҪңз”Ёзҡ„дәәжҠҘе‘ҠеҸӘжңүйқһеёёиҪ»еҫ®зҡ„еүҜдҪңз”ЁгҖӮ1992жі•еӣҪзҡ„дёҖзҜҮжі•еӣҪжҠҘйҒ“иҜҙ50%еҒңжӯўдҪҝз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„еҰҮеҘіжҳҜеӣ дёәжңҲз»ҸдёҚи°ғ пјҢдҫӢеҰӮзӘҒз ҙеҮәиЎҖжҲ–иҖ…жңҲз»ҸеҒңжӯўгҖӮ[ 66]

иӢұеӣҪThe GPs Oral Contraception Studyз ”з©¶жҳҫзӨә45еІҒд№ӢеүҚеҒңжӯўжңҚиҚҜ5-9е№ҙд№ӢеүҚзҡ„еҰҮеҘіжңүз•Ҙеҫ®й«ҳжҜ”дҫӢзҡ„жӯ»дәЎзҺҮгҖӮдҪҶе№ҙзәӘеӨ§дёҖдәӣеҗҺиҝҷдәӣжңҚз”ЁиҝҮйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„еҰҮеҘізҡ„жӯ»дәЎзҺҮжҳҫи‘—дёӢйҷҚгҖӮ

жӯӨйЎ№зӣ®зҡ„з ”з©¶иҖ…иҜҙпјҢйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеҸҜд»Ҙжңүж•Ҳйў„йҳІиӮ йҒ“гҖҒеӯҗе®«е’ҢеҚөе·ўзҷҢгҖӮдҪҶHannafordж•ҷжҺҲжҺЁж–ӯеҺҹеӣ д№ҹжңүеҸҜиғҪжңҚз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„еҰҮеҘіжӣҙе…іеҝғиҮӘе·ұзҡ„еҒҘеә·пјҢеҒҡжӣҙеӨҡзҡ„дҪ“жЈҖгҖӮд»–иҜҙвҖңиҝҷдёӘз ”з©¶еёҰжқҘзҡ„дҝЎжҒҜжҳҜпјҢеҰӮжһңеҰҮеҘій•ҝжңҹжңҚз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜпјҢ他们зҡ„еҒҘеә·й—®йўҳзҡ„йЈҺйҷ©е№¶жІЎжңүеўһеҠ пјҢз”ҡиҮіеҜ№еҒҘеә·жӣҙжңүзӣҠвҖқпјҢдҪҶжҳҜвҖңжҲ‘们并дёҚжҺЁиҚҗеҰҮеҘіз”ЁжңҚз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„еҠһжі•йҳІжІ»зӣёе…ізҷҢз—ҮвҖқ[ 67]

иҜ·и§Ғ#жіЁж„ҸдәӢйЎ№е’ҢзҰҒеҝҢз—Ү дёҖиҠӮ

е…ідәҺд№іи…әзҷҢ йЈҺйҷ©е’ҢиҚ·е°”и’ҷзұ»йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„з ”з©¶жҳҜеӨҚжқӮиҖҢзңӢдјјзҹӣзӣҫзҡ„гҖӮ[ 68] [ 69] [ 69]

1996е№ҙзҡ„дёҖдёӘеҜ№жҖ»ж•°и¶…иҝҮ15дёҮеҰҮеҘіпјҢ54 дёӘд№іи…әзҷҢз ”з©¶зҡ„з»јеҗҲж•°жҚ®еҲҶжһҗеҸ‘зҺ°пјҡвҖңеҲҶжһҗз»“жһңжҸҗдҫӣзҡ„жңүеҠӣиҜҒжҚ®иЎЁжҳҺдёӨдёӘдё»иҰҒз»“и®әпјҡ第дёҖпјҢжӯЈеңЁжңҚз”ЁеӨҚж–№еҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜе’Ңе·Із»ҸеҒңиҚҜ10е№ҙд»ҘеҶ…зҡ„еҰҮеҘіеўһеҠ дәҶеҫҲе°Ҹзҡ„иў«иҜҠж–ӯ еҮәд№іи…әзҷҢзҡ„йЈҺйҷ©гҖӮ第дәҢпјҢеҜ№дәҺеҒңиҚҜ10е№ҙд»ҘеҗҺзҡ„еҰҮеҘізҡ„йЈҺйҷ©еҲҷжІЎжңүжҳҺжҳҫеўһеҠ гҖӮеңЁе·Із»Ҹиў«зЎ®иҜҠд№іи…әзҷҢзҡ„еҰҮеҘідёӯпјҢжңҚз”ЁеӨҚеҗҲеҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„жҜ”д»ҺжңӘз”ЁиҚҜзҡ„дәәжӣҙж—©зҡ„иў«иҜҠж–ӯеҮәжқҘгҖӮвҖқ[ 4] дё”жңҚз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•и—Ҙзҡ„еҰҮеҘійҖҡеёёжӣҙжіЁйҮҚиҮӘиә«еҒҘеә·дёҰеҒҡдәҶжӣҙеӨҡзҡ„еҰҮ科жЈҖжҹҘ [еҸҜз–‘ пјҢеӣ жӯӨжӣҙе®№жҳ“еҸ‘зҺ°ж—©жңҹзҡ„д№іи…әзҷҢиҖҢйқһжң«жңҹиҪү移гҖӮ[ 70] [ 71] [е·ІиҝҮж—¶

йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеҜ№дҪ“йҮҚзҡ„еҪұе“Қдё»иҰҒжҳҜз”ұ1970е№ҙд»ЈйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеӨҡжңүдёҖе®ҡйӣ„жҝҖзҙ жҙ»жҖ§йҖ жҲҗзҡ„пјҢиҖҢж–°еһӢйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜдёӯзҡ„еӯ•жҝҖзҙ еҜ№йӣ„жҝҖзҙ еҸ—дҪ“жІЎжңүдәІе’ҢеҠӣпјҢдёҚдјҡеўһйҮҚгҖӮ[ 57]

1992е№ҙжі•еӣҪдёҖзҜҮж–Үз« жҠҘйҒ“дәҶдёҖз»„15вҖ“19еІҒйқ’е°‘е№ҙ еңЁ1982е№ҙеҒңжӯўз”ЁиҚҜзҡ„и°ғжҹҘжҠҘе‘ҠпјҢ20вҖ“25% жҠҘе‘ҠиҜҙеӣ дёәдҪ“йҮҚеўһеҠ иҝҳжңү25%еӣ дёәе®іжҖ•еҫ—зҷҢз—Ү гҖӮ[ 66]

д»ҠеӨ©пјҢеҫҲеӨҡеҢ»з”ҹйғҪи®ӨдёәеӨ§дј—и®ӨдёәйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜйҖ жҲҗдҪ“йҮҚеўһеҠ зҡ„жғіжі•жҳҜдёҚжӯЈзЎ®з”ҡиҮіеҚұйҷ©зҡ„гҖӮдёҖзҜҮиӢұеӣҪз ”з©¶жҖ»з»“иҜҙжІЎжңүд»»дҪ•иҜҒжҚ®иЎЁйқўзҺ°д»ЈдҪҺеүӮйҮҸйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜдјҡеҜјиҮҙдҪ“йҮҚеўһеҠ пјҢдҪҶжҳҜеӣ дёәжӢ…еҝғдҪ“йҮҚеўһеҠ еҚҙдјҡеҜјиҮҙеҒңиҚҜиҖҢж„ҸеӨ–жҖҖеӯ•пјҢеҜ№дәҺе°‘еҘіжқҘиҜҙиҝҷз§ҚзҺ°иұЎе°Өе…¶дёҘйҮҚгҖӮ[ 14]

еӨҚеҗҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеҜ№жҖ§иғҪеҠӣеҸҜиғҪжңүеҘҪзҡ„жҲ–иҖ…еқҸзҡ„еҪұе“ҚгҖӮеҰҮеҘіеӣ дёәдёҚз”ЁжӢ…еҝғжҖҖеӯ• пјҢеңЁеҝғзҗҶ дёҠеҸҜд»Ҙе°Ҫжғ…дә«еҸ—жҖ§зҡ„еҝ«д№җгҖӮеӨҚеҗҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеҸҜиғҪдҪҝйҳҙйҒ“ жӣҙеҠ ж¶Ұж»‘пјӣдҪҶд№ҹжңүеҰҮеҘіжҠҘе‘ҠиҜҙжҖ§ж…ҫдҪҺдёӢиҖҢеҜјиҮҙйҳҙйҒ“ е№ІзҮҘгҖӮ[ 72] [ 73]

еҜ№дәҺе·Із»Ҹж·ҳжұ°зҡ„й•ҝж•ҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜжүҚжңүеҒңиҚҜ3вҖ•6дёӘжңҲеҶҚеҰҠеЁ зҡ„иҜҙжі•гҖӮдҪҶеҜ№дәҺзҺ°д»ЈеӨҚеҗҲйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜпјҢжІЎжңүд»»дҪ•дёҙеәҠз ”з©¶иҜҒжҳҺйңҖиҰҒеҒңиҚҜгҖӮвҖқз ”з©¶еҸ‘зҺ°пјҢжңҚз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„еҰҮеҘіжҖҖеӯ•з”ҹдә§еҗҺпјҢеҗҺд»ЈеҮәзҺ°е…ҲеӨ©жҖ§еҝғи„Ҹзјәйҷ· е’ҢиӮўдҪ“зҹӯе°Ҹ зҡ„йЈҺйҷ©дёҺжІЎжңүжңҚиҝҮйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„еҰҮеҘізҡ„еӯ©еӯҗзӣёжҜ”пјҢеҹәжң¬жІЎжңүе·®еҲ«гҖӮйғ‘ж·‘и“үж•ҷжҺҲи®ӨдёәпјҢйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜиғҪжңүж•ҲйҳІжӯўејӮдҪҚеҰҠеЁ пјҢйҳ»жӯўдёӢз”ҹж®–йҒ“ж„ҹжҹ“зҷјеұ•дёәзӣҶи…”ж„ҹжҹ“ пјҢеҜ№дҝқжҠӨеҘіжҖ§з”ҹиӮІиғҪеҠӣжңүеҘҪеӨ„гҖӮ[ 57]

еӨ§и„‘ дёӯиЎҖжё…зҙ зҡ„еҗ«йҮҸжҳҜеҪұе“Қеҝ§йғҒз—Ү зҡ„йҮҚиҰҒеӣ зҙ гҖӮж—©жңҹзҡ„йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеҗ«жңүеӨ§йҮҸжҝҖзҙ пјҢиў«иҜҒжҳҺдјҡжҳҫи‘—йҷҚдҪҺеӨ§и„‘иЎҖжё…зҙ ж°ҙе№ігҖӮ[ 60] [ 74] [ 60] [ 75]

еӯ•жҝҖзҙ дјҡеҪұе“ҚдҪ“еҶ…ж°ЁеҹәиӮҪй…¶ зҡ„ж°ҙе№іпјҢиҝҷз§Қй…¶ еҸҜиғҪз ҙеқҸиЎҖз®ЎиҲ’зј“жҝҖиӮҪ пјҢжңҖз»ҲжңүеҸҜиғҪжҸҗй«ҳй«ҳиЎҖеҺӢ зҡ„йЈҺйҷ©гҖӮ[ 76]

е°ұеғҸеҰҮеҘіз”ҹиӮІеҗҺи„ұеҸ‘дёҖж ·пјҢеҒңжӯўжңҚз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеҗҺеҘіжҖ§дҪ“еҶ…жҝҖзҙ зҡ„еҸҳеҢ–еҸҜиғҪеҜјиҮҙзҹӯж—¶й—ҙзҡ„и„ұеҸ‘пјҢдҪҶиҝҮдёҖж®өж—¶й—ҙе°ұдјҡй•ҝеӣһжқҘгҖӮ[ 77]

еҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜиҝҳеҸҜд»Ҙйў„йҳІзӣҙиӮ зҷҢ пјҢжІ»з–—зӣҶи…”зӮҺ гҖҒз—ӣз»Ҹ гҖҒз»ҸеүҚз»јеҗҲз—Ү е’ҢзІүеҲә гҖӮ[ 78] еӯҗе®«еҶ…иҶңејӮдҪҚ е’ҢеӨҡеӣҠеҚөе·ўз»јеҗҲз—Ү е’Ңиҙ«иЎҖ зҡ„з—ҮзҠ¶гҖӮ[ 79]

жҚ®йҳҝдјҜдёҒеӨ§еӯҰ Philip Hannafordж•ҷжҺҲйўҶеҜјзҡ„the Royal College of GPs Oral Contraception Studyз ”з©¶е°Ҹз»„еңЁиӢұеӣҪеҢ»еӯҰжңҹеҲҠпјҲBritish Medical JournalпјүдёҠеҸ‘иЎЁзҡ„жңҖж–°з ”з©¶жҲҗжһңпјҡз»ҸиҝҮ40е№ҙзҡ„з ”з©¶пјҢз»ҹи®ЎдәҶи¶…иҝҮ46,000дёӘеҰҮеҘіиҝӣиЎҢеҜ№жҜ”иҜ•йӘҢпјҢеҸ‘зҺ°жҜҸ100,000жңҚз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„еҰҮеҘідёӯпјҢжҜ”е…¶д»–йҒҝеӯ•ж–№ејҸзҡ„е№іеқҮе°‘жӯ»дәЎ52дәә

[ 80] [ 67]

з ”з©¶иЎЁжҳҺдҪҝз”ЁеҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜиҮіе°‘5е№ҙд»ҘдёҠпјҢеҸҜд»ҘдҪҝд»ҘеҗҺдёҖз”ҹеҫ—еҚөе·ўзҷҢ зҡ„еҮ зҺҮйҷҚдҪҺ50%гҖӮ[ 81] [ 62]

еҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеҸҜиғҪдјҡеҪұе“ҚеҮқиЎҖ пјҢеӣ дёәе…¶дёӯзҡ„йӣҢжҝҖзҙ еҪұе“ҚдәҶеҮқиЎҖеӣ еӯҗзҡ„еҗҲжҲҗпјҢеўһеҠ ж·ұйқҷи„үиЎҖж “ пјҲDVTпјүе’ҢиӮәж “еЎһ пјҢдёӯйЈҺ е’ҢеҝғиӮҢжў—жӯ» зҡ„йЈҺйҷ©гҖӮдёҖиҲ¬иў«и®ӨдёәеӨҚж–№еҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„зҰҒеҝҢз—Үдёәпјҡе·Із»ҸеҸ‘з—…зҡ„еҝғиЎҖз®Ўз–ҫз—… жӮЈиҖ…гҖҒ家ж—ҸеҶ…жңүеҘіжҖ§иЎҖж “зұ»з—…еҸІпјҲеҰӮйҒ—дј еӣ еӯҗV Leiden зӘҒеҸҳпјүгҖҒй«ҳиғҶеӣәйҶҮиЎҖз—Ү пјҲй«ҳиғҶеӣәйҶҮпјүгҖҒ35еІҒд»ҘдёҠзҡ„еҗёзғҹиҖ… пјҢд»ҘеҸҠз”ҹиӮІеҗҺ21еӨ©еҶ…зҡ„еҰҮеҘіпјҲжҲ–е“әд№іжңҹзҡ„28еӨ©еҶ…зҡ„пјҢжҲ–жңүиЎҖж “йЈҺйҷ©зҡ„пјҢеңЁз”ҹиӮІеҗҺзҡ„42еӨ©еҶ…дёҚеҫ—жңҚз”ЁгҖӮйЈҺйҷ©еӣ зҙ еҢ…жӢ¬иӮҘиғ–жҲ–иҝӣиЎҢиҝҮеү–и…№дә§пјүгҖӮ[ 82] [ 83] [ 84] иӮҘиғ– дёҚиў«и®ӨдёәжҳҜдҪҝз”ЁйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„зҰҒеҝҢз—ҮгҖӮ[ 85]

еҢ»еӯҰжқғеЁҒзҺ°еңЁе·Із»Ҹжҷ®йҒҚжҺҘеҸ—жңҚз”ЁеҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеҜ№еҒҘеә·йҖ жҲҗзҡ„йЈҺйҷ©дҪҺдәҺжҖҖеӯ•е’Ңз”ҹиӮІ[ 86] дё–з•ҢеҚ«з”ҹз»„з»Ү )[ 87] [ 88]

йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜзҡ„иҚ·е°”и’ҷеҸҜд»Ҙз”ЁжқҘжІ»з–—дёҖдәӣдёҙеәҠз–ҫз—…пјҢеҰӮеӨҡеӣҠеҚөе·ўз»јеҗҲеҫҒ пјҲPCOSпјүзҡ„пјҢеӯҗе®«еҶ…иҶңејӮдҪҚз—Ү пјҢеӯҗе®«и…әиӮҢз—… пјҢдёҺжңҲз»Ҹиҙ«иЎҖпјҢз—ӣз»Ҹ гҖӮжӯӨеӨ–пјҢеҸЈжңҚйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜжҳҜжІ»з–—иҪ»еәҰжҲ–дёӯеәҰз—Өз–®зҡ„常规иҚҜзү©гҖӮ йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜд№ҹеҸҜд»Ҙи°ғж•ҙдёҚ规еҲҷе’ҢејӮеёёзҡ„жңҲз»Ҹе‘ЁжңҹпјҢе’ҢеҠҹиғҪеӨұи°ғжҖ§еӯҗе®«еҮәиЎҖ гҖӮжӯӨеӨ–пјҢйҒҝеӯ•иҚҜжҸҗдҫӣдәҶдёҖдәӣеҜ№йқһзҷҢз—Үзҡ„д№іжҲҝеҸ‘иӮІдҝқжҠӨпјҢйҳІжӯўе®«еӨ–еӯ•е’ҢйҳҙйҒ“е№ІзҮҘпјҢе’Ңжӣҙе№ҙжңҹжңүе…ізҡ„жҖ§дәӨз–јз—ӣгҖӮ[ 89]

^ 1.0 1.1 Trussell, James. Contraceptive efficacy. Hatcher, Robert A.; Trussell, James; Nelson, Anita L.; Cates, Willard Jr.; Kowal, Deborah; Policar, Michael S. (eds.) (зј–). Contraceptive technology 20th revised. New York: Ardent Media. 2011: 779вҖ“863. ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0ISSN 0091-9721 OCLC 781956734 Table 3вҖ“2 Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of typical use and the first year of perfect use of contraception, and the percentage continuing use at the end of the first year. United States. пјҲйЎөйқўеӯҳжЎЈеӨҮд»Ҫ пјҢеӯҳдәҺдә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ пјү^ 2.0 2.1 Hannaford, Philip C.; Iversen, Lisa; Macfarlane, Tatiana V.; Elliot, Alison; Angus, Valerie; Lee, Amanda J. Mortality among contraceptive pill users: cohort evidence from Royal College of General Practitioners' Oral Contraception Study . BMJ. March 11, 2010, 340 : c927. PMC 2837145 PMID 20223876 doi:10.1136/bmj.c927 ^ IARC working group. Combined Estrogen-Progestogen Contraceptives (PDF) . IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (International Agency for Research on Cancer ). 2007, 91 [2014-04-21 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2016-08-03пјү. ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet . 1996, 347 (9017): 1713вҖ“27. PMID 8656904 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90806-5 ^ Kemmeren, J. M.; Tanis, BC; Van Den Bosch, MA; Bollen, EL; Helmerhorst, FM; Van Der Graaf, Y; Rosendaal, FR; Algra, A. Risk of Arterial Thrombosis in Relation to Oral Contraceptives (RATIO) Study: Oral Contraceptives and the Risk of Ischemic Stroke . Stroke. 2002, 33 (5): 1202вҖ“8. PMID 11988591 doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000015345.61324.3F ^ Baillargeon, J.-P. Association between the Current Use of Low-Dose Oral Contraceptives and Cardiovascular Arterial Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005, 90 (7): 3863вҖ“70. PMID 15814774 doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1958 ^ Planned Parenthood - Birth Control Pills . [2014-04-21 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2011-08-05пјү. ^ 8.0 8.1 UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Trends in Contraceptive Use Worldwide 2015 (PDF) . New York: United Nations. 2015: 51 [2019-07-23 ] . ISBN 978-92-1-151546-6еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2020-02-14пјү. ^ иЎҢж”ҝйҷўжҖ§еҲҘе№ізӯүжңғ-жҖ§еҲҘзөұиЁҲиіҮж–ҷеә« . www.gender.ey.gov.tw. [2019-07-23 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2020-08-09пјү. ^ Mosher WD, Martinez GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Willson SJ. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982вҖ“2002 (PDF) . Adv Data. 2004, (350): 1вҖ“36 [2010-03-12 ] . PMID 15633582 еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2021-01-26пјү. ^ Contraceptive Use in the United States . Guttmacher Institute. 2018-07 [2019-07-23 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2016-12-11пјү пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ Taylor, Tamara; Keyse, Laura; Bryant, Aimee. Contraception and Sexual Health, 2005/06 (PDF) . London: Office for National Statistics. 2006. ISBN 1-85774-638-4еҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (PDF) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2007-01-09пјү. ^ Yoshida H, Sakamoto H, Leslie A, Takahashi O, Tsuboi S, Kitamura K. Contraception in Japan: Current trends. Contraception. June 2016, 93 (6): 475вҖ“7. PMID 26872717 doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.02.006 ^ 14.0 14.1 Gupta S. Weight gain on the combined pillвҖ”is it real?. Hum Reprod Update. 2000, 6 (5): 427вҖ“31. PMID 11045873 doi:10.1093/humupd/6.5.427 ^ IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Hormonal contraceptives, progestogens only . Hormonal contraception and post-menopausal hormonal therapy; IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, Volume 72. Lyon: IARC Press. 1999: 339вҖ“397 [2010-03-15 ] . ISBN 92-832-1272-XеӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2006-09-28пјү. ^ Goldzieher JW, Rudel HW. How the oral contraceptives came to be developed. JAMA . 1974, 230 (3): 421вҖ“5. PMID 4606623 doi:10.1001/jama.230.3.421 ^ Goldzieher JW. Estrogens in oral contraceptives: historical perspective . Johns Hopkins Med J. 1982, 150 (5): 165вҖ“9. PMID 7043034 ^ Perone N. The history of steroidal contraceptive development: the progestins . Perspect Biol Med. 1993, 36 (3): 347вҖ“62. PMID 8506121 ^ Goldzieher JW. The history of steroidal contraceptive development: the estrogens . Perspect Biol Med. 1993, 36 (3): 363вҖ“8. PMID 8506122 ^ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Pincus G, Bialy G. Drugs Used in Control of Reproduction. Adv Pharmacol. 1964, 3 : 285вҖ“313. PMID 14232795 doi:10.1016/S1054-3589(08)61115-1 The original observation of Makepeace et al. (1937) that progesterone inhibited ovulation in the rabbit was substantiated by Pincus and Chang (1953). In women, 300 mg of progesterone per day taken orally resulted in ovulation inhibition in 80% of cases (Pincus, 1956). The high dosage and frequent incidence of breakthrough bleeding limited the practical application of the method. Subsequently, the utilization of potent 19-norsteroids, which could be given orally, opened the field to practical oral contraception. ^ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Maisel, Albert Q. The Hormone Quest . New York: Random House. 1965. ^ 22.0 22.1 Asbell, Bernard. The Pill: A Biography of the Drug That Changed the World . New York: Random House. 1995. ISBN 0-679-43555-7 еј•з”Ёй”ҷиҜҜпјҡеёҰжңүnameеұһжҖ§вҖңasbellвҖқзҡ„<ref>ж Үзӯҫз”ЁдёҚеҗҢеҶ…е®№е®ҡд№үдәҶеӨҡж¬Ў ^ Freudenheim, Milt. COMPANY NEWS; Roche Set To Acquire Syntex . The New York Times. 1994-05-03 [2019-07-23 ] . ISSN 0362-4331 еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2019-08-15пјү пјҲзҫҺеӣҪиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ еј•з”Ёй”ҷиҜҜпјҡжІЎжңүдёәеҗҚдёәSperoff 20052зҡ„еҸӮиҖғж–ҮзҢ®жҸҗдҫӣеҶ…е®№

^ Lehmann PA, Bolivar A, Quintero R. Russell E. Marker. Pioneer of the Mexican steroid industry . Journal of Chemical Education. March 1973, 50 (3): 195вҖ“9. Bibcode:1973JChEd..50..195L PMID 4569922 doi:10.1021/ed050p195 ^ 26.0 26.1 Vaughan P. The Pill on Trial . New York: Coward-McCann. 1970. OCLC 97780 ^ Tone A. Devices & Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America . New York: Hill and Wang. 2001. ISBN 978-0-8090-3817-6 ^ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Reed J. From Private Vice to Public Virtue: The Birth Control Movement and American Society Since 1830 . New York: Basic Books. 1978. ISBN 978-0-465-02582-4 ^ 29.0 29.1 McLaughlin L. The Pill, John Rock, and the Church: The Biography of a Revolution . Boston: Little, Brown. 1982. ISBN 978-0-316-56095-5 ^ Marks L. Sexual Chemistry: A History of the Contraceptive Pill . New Haven: Yale University Press. 2001. ISBN 978-0-300-08943-1 ^ Watkins ES. On the Pill: A Social History of Oral Contraceptives, 1950вҖ“1970 . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 1998. ISBN 978-0-8018-5876-5 ^ Djerassi C. This Man's Pill: Reflections on the 50th Birthday of the Pill . Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2001: 11 вҖ“62. ISBN 978-0-19-850872-4 ^ Applezweig N. Steroid Drugs . New York: Blakiston Division, McGraw-Hill. 1962: viiвҖ“xi, 9вҖ“83. OCLC 14615096 ^ Gereffi G. The Pharmaceutical Industry and Dependency in the Third World . Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1983: 53 вҖ“163. ISBN 978-0-691-09401-4 ^ 35.0 35.1 Chang MC. Development of the oral contraceptives. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. September 1978, 132 (2): 217вҖ“9. PMID 356615 doi:10.1016/0002-9378(78)90928-6 ^ Fields A. Katharine Dexter McCormick: Pioneer for Women's Rights . Westport, Conn.: Prager. 2003. ISBN 978-0-275-98004-7 ^ Rock J, Garcia CR, Pincus G. Synthetic progestins in the normal human menstrual cycle. Recent Progress in Hormone Research. 1957, 13 : 323вҖ“39; discussion 339вҖ“46. PMID 13477811 ^ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Pincus G. The hormonal control of ovulation and early development . Postgraduate Medicine. December 1958, 24 (6): 654вҖ“60. PMID 13614060 doi:10.1080/00325481.1958.11692305 ^ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Pincus, Gregory. Progestational Agents and the Control of Fertility 17 : 307вҖ“324. 1959. ISSN 0083-6729 doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(08)60274-5 Ishikawa et al. (1957) employing the same regime of progesterone administration also observed suppression of ovulation in a proportion of the cases taken to laparotomy. Although sexual intercourse was practised freely by the subjects of our experiments and those of Ishikawa el al., no pregnancies occurred. Since ovulation presumably took place in a proportion of cycles, the lack of any pregnancies may be due to chance, but Ishikawa et al. (1957) have presented data indicating that in women receiving oral progesterone the cervical mucus becomes impenetrable to sperm. ^ 40.0 40.1 Diczfalusy E. Probable mode of action of oral contraceptives . Br Med J. December 1965, 2 (5475): 1394вҖ“9. PMC 1847181 PMID 5848673 doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5475.1394 At the Fifth International Conference on Planned Parenthood in Tokyo, Pincus (1955) reported an ovulation inhibition by progesterone or norethynodrel1 taken orally by women. This report indicated the beginning of a new era in the history of contraception. [...] That the cervical mucus might be one of the principal sites of action was suggested by the first studies of Pincus (1956, 1959) and of Ishikawa et al. (1957). These investigators found that no pregnancies occurred in women treated orally with large doses of progesterone, though ovulation was inhibited only in some 70% of the cases studied. [...] The mechanism of protection in this methodвҖ”and probably in that of Pincus (1956) and of Ishikawa et al. (1957)вҖ”must involve an effect on the cervical mucus and/or endometrium and Fallopian tubes. ^ 41.0 41.1 Annette B. RamГӯrez de Arellano; Conrad Seipp. Colonialism, Catholicism, and Contraception: A History of Birth Control in Puerto Rico . University of North Carolina Press. 10 October 2017: 107вҖ“ [2019-07-23 ] . ISBN 978-1-4696-4001-3еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2021-06-25пјү. [...] Still, neither of the two researchers was completely satisfied with the results. Progesterone tended to cause "premature menses," or breakthrough bleeding, in approximately 20 percent of the cycles, an occurrence that disturbed the patients and worried Rock.17 In addition, Pincus was concerned about the failure to inhibit ovulation in all the cases. Only large doses of orally administered progesterone could insure the suppression of ovulation, and these doses were expensive. The mass use of this regimen as a birth control method was thus seriously imperiled.18 [...] ^ Garcia CR, Pincus G, Rock J. Effects of certain 19-nor steroids on the normal human menstrual cycle . Science. November 1956, 124 (3227): 891вҖ“3. Bibcode:1956Sci...124..891R PMID 13380401 doi:10.1126/science.124.3227.891 ^ 43.0 43.1 Rock J, GarcГӯa CR. Observed effects of 19-nor steroids on ovulation and menstruation. Proceedings of a Symposium on 19-Nor Progestational Steroids. Chicago: Searle Research Laboratories. 1957: 14вҖ“31. OCLC 935295 ^ Pincus G, Rock J, Garcia CR, Ricewray E, Paniagua M, Rodriguez I. Fertility control with oral medication . American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. June 1958, 75 (6): 1333вҖ“46. PMID 13545267 doi:10.1016/0002-9378(58)90722-1 ^ Segal SJ. The Pill and the IUD Modernized Contraception. Under the Banyan Tree: A Population Scientist's Odyssey . Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2003: 70 78 ISBN 978-0-19-515456-6 ^ GarcГӯa CR. Development of the pill. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. December 2004, 1038 : 223вҖ“6. Bibcode:2004NYASA1038..223G PMID 15838117 doi:10.1196/annals.1315.031 ^ Strauss JF, Mastroianni L. In memoriam: Celso-Ramon Garcia, M.D. (1922-2004), reproductive medicine visionary . Journal of Experimental & Clinical Assisted Reproduction. January 2005, 2 (1): 2. PMC 548289 PMID 15673473 doi:10.1186/1743-1050-2-2 ^ Junod SW, Marks L. Women's trials: the approval of the first oral contraceptive pill in the United States and Great Britain (PDF) . Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. April 2002, 57 (2): 117вҖ“60 [2019-07-23 ] . PMID 11995593 doi:10.1093/jhmas/57.2.117 еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2012-07-03пјү. ^ RamГӯrez de Arellano AB, Seipp C. Colonialism, Catholicism, and Contraception: A History of Birth Control in Puerto Rico. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 1983. ISBN 978-0-8078-1544-1 ^ Rice-Wray E. Field Study with Enovid as a Contraceptive Agent. Proceedings of a Symposium on 19-Nor Progestational Steroids. Chicago: Searle Research Laboratorie. 1957: 78вҖ“85. OCLC 935295 ^ Marsh M, Ronner W. The Fertility Doctor: John Rock and the Reproductive Revolution . Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 2008: 188 вҖ“197. ISBN 978-0-8018-9001-7 ^ The Puerto Rico Pill Trials . [2019-01-19 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2021-03-03пјү. ^ Tyler ET, Olson HJ. Fertility promoting and inhibiting effects of new steroid hormonal substances. Journal of the American Medical Association. April 1959, 169 (16): 1843вҖ“54. PMID 13640942 doi:10.1001/jama.1959.03000330015003 ^ Winter IC. Summary. Proceedings of a Symposium on 19-Nor Progestational Steroids. Chicago: Searle Research Laboratories. 1957: 120вҖ“122. OCLC 935295 ^ Djerassi on birth control in Japan - abortion 'yes,' pill 'no' (ж–°й—»зЁҝ). Stanford University News Service. 96-14-02 [2006-08-23 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2007-01-06пјү. ^ 56.0 56.1 еј•з”Ёй”ҷиҜҜпјҡжІЎжңүдёәеҗҚдёәcbsзҡ„еҸӮиҖғж–ҮзҢ®жҸҗдҫӣеҶ…е®№

^ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 йқ’жңЁпјҢеҗҙзҝ”. йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜиў«дёӯеӣҪдәәиҜҜи§ЈдәҶ дёҚеўһйҮҚиҝҳиғҪйҳІзҷҢ . дәәж°‘зҪ‘вҖ•гҖҠз”ҹе‘Ҫж—¶жҠҘгҖӢ. 2006-04-25: 24 [2010-03-12 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2016-03-04пјү. ^ Organon . Mercilon SPC (Summary of Product Characteristics . November 2001 [2007-04-07 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2007-09-28пјү. ^ Stacey, Dawn. Birth Control Pills йЎөйқўеӯҳжЎЈеӨҮд»Ҫ пјҢеӯҳдәҺдә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ пјү Accessed July 20, 2009

^ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 Trussell, James. Contraceptive Efficacy . Hatcher, Robert A.; et al (зј–). Contraceptive Technology 19th rev. New York: Ardent Media. 2007 [2010-03-12 ] . ISBN 0-9664902-0-7еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2008-05-31пјү. ^ Skouby, SO. The European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care (2004) "Contraceptive use and behavior in the 21st century: a comprehensive study across five European countries." 9(2):57-68

^ 62.0 62.1 Speroff, Leon; Darney, Philip D. Oral Contraception. A Clinical Guide for Contraception 4th. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 21вҖ“138. ISBN 0-781-76488-2 ^ Loose, Davis S.; Stancel, George M. Estrogens and Progestins. Brunton, Laurence L.; Lazo, John S.; Parker, Keith L. (eds.) (зј–). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics 11th. New York: McGraw-Hill. 2006: 1541 вҖ“1571. ISBN 0-07-142280-3 ^ Glasier, Anna. Contraception. DeGroot, Leslie J.; Jameson, J. Larry (eds.) (зј–). Endocrinology 5th. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. 2006: 2993вҖ“3003. ISBN 0-7216-0376-9 ^ 65.0 65.1 Rivera R, Yacobson I, Grimes D. The mechanism of action of hormonal contraceptives and intrauterine contraceptive devices. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999, 181 (5 Pt 1): 1263вҖ“9. PMID 10561657 doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70120-1 ^ 66.0 66.1 Serfaty D. Medical aspects of oral contraceptive discontinuation. Adv Contracept. 1992, 8 (Suppl 1): 21вҖ“33. PMID 1442247 doi:10.1007/BF01849448 Sanders, Stephanie A.; Cynthia A. Graham, Jennifer L. Bass and John Bancroft. A prospective study of the effects of oral contraceptives on sexuality and well-being and their relationship to discontinuation . Contraception. July 2001, 64 (1): 51вҖ“58 [2007-03-02 ] . PMID 11535214 doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00218-9 ^ 67.0 67.1 Jo Steele. Take The Pill 'for a long life' . London Metro. 2010-03-12. ^ FPA. The combined pill - Are there any risks? . Family Planning Association (UK). April 2005 [2007-01-08 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2007-02-08пјү. ^ 69.0 69.1 The Pill and Breast Cancer Risk . WebMD. [2019-07-23 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2020-11-28пјү пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: further results. Contraception. 1996, 54 (3 Suppl): 1SвҖ“106S. PMID 8899264 ^ Plu-Bureau G, LГӘ M. Oral contraception and the risk of breast cancer. Contracept Fertil Sex. 1997, 25 (4): 301вҖ“5. PMID 9229520 ^ Hatcher & Nelson. Combined Hormonal Contraceptive Methods. Hatcher, Robert D. (зј–). Contraceptive technology 18th. New York: Ardent Media, Inc. 2004: 403,432,434. ISBN 0-9664902-5-8 ^ Darney, Philip D.; Speroff, Leon. A clinical guide for contraception 4th. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005: 72. ISBN 0-7817-6488-2 ^ Katherine Burnett-Watson. Is The Pill Playing Havoc With Your Mental Health? . October 2005 [2007-03-20 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2007-03-20пјү. Kulkarni J, Liew J, Garland K. Depression associated with combined oral contraceptivesвҖ”a pilot study. Aust Fam Physician. 2005, 34 (11): 990. PMID 16299641 ^ Rose DP, Adams PW. Oral contraceptives and tryptophan metabolism: effects of oestrogen in low dose combined with a progestagen and of a low-dose progestagen (megestrol acetate) given alone . J. Clin. Pathol. March 1972, 25 (3): 252вҖ“8. PMC 477273 PMID 5018716 doi:10.1136/jcp.25.3.252 ^ еӯҳжЎЈеүҜжң¬ . [2010-03-12 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2019-05-23пјү. ^ Female hair loss treatment hope . 2006-03-21 [2010-03-15 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2021-02-14пјү. ^ Huber JC, Bentz EK, Ott J, Tempfer CB. Non-contraceptive benefits of oral contraceptives . Expert Opin Pharmacother. September 2008, 9 (13): 2317вҖ“25. PMID 18710356 doi:10.1517/14656566.9.13.2317 еҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2013-01-11пјү. ^ An Introduction to Behavioral Endocrinology, Randy J Nelson, 3rd edition, Sinauer

^ Daniel Martin. Is the Pill saving lives? Women who use it 'cut their chances of dying of cancer and heart disease' . Daily Mail. 2010-03-12 [2010-03-12 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2021-01-26пјү. ^ Bast RC, Brewer M, Zou C; et al. Prevention and early detection of ovarian cancer: mission impossible?. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2007, 174 : 91вҖ“100. PMID 17302189 doi:10.1007/978-3-540-37696-5_9 ^ жҝҖзҙ йҒҝеӯ•ж–№жі• . й»ҳе…ӢиҜҠз–—жүӢеҶҢ家еәӯзүҲ. [2019-07-23 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2019-03-29пјү пјҲдёӯж–Үпјү . ^ AOGSпјҡйҖүжӢ©йҒҝеӯ•иҚҜеә”иҖғиҷ‘иЎҖж “йЈҺйҷ© . yao.dxy.cn. [2019-07-23 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2019-07-23пјү. ^ Lidegaard, Гҳjvind; Milsom, Ian; Geirsson, Reynir Tomas; Skjeldestad, Finn Egil. Hormonal contraception and venous thromboembolism . Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2012-7, 91 (7): 769вҖ“778 [2019-07-23 ] . ISSN 1600-0412 PMID 22568831 doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01444.x еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2019-07-23пјү. ^ World Health Organization. Reproductive Health and Research. Selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use Third. Geneva. 2017-01-12: 150. ISBN 9789241565400OCLC 985676200 ^ Crooks, Robert L. and Karla Baur. Our Sexuality . Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. 2005. ISBN 0-534-65176-3 ^ WHO (2005). Decision-Making Tool for Family Planning Clients and Providers пјҲйЎөйқўеӯҳжЎЈеӨҮд»Ҫ пјҢеӯҳдәҺдә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ пјү Appendix 10: Myths about contraception^ Holck, Susan. Contraceptive Safety . Special Challenges in Third World Women's Health. 1989 Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association. [2006-10-07 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2017-11-08пјү. ^ Huber J, Walch K. Treating acne with oral contraceptives: use of lower doses. . Contraception. 2006, 73 (1): 23вҖ“9. PMID 16371290 doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2005.07.010